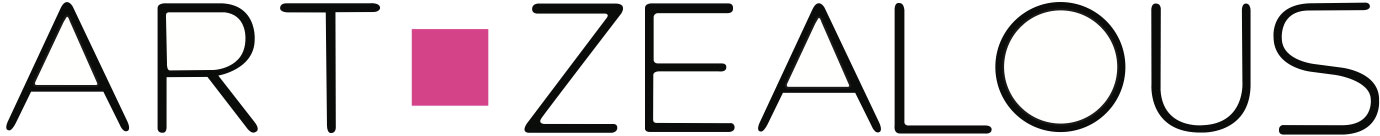

Painting or print—can you tell which one is which? These images are details from works by Colbert Mashile and Guy Buffet.

When you’re new to art, one of the biggest challenges is understanding prints. To the untrained eye, they can look the same as other kinds of works. So how can you tell the difference between prints, paintings, and drawings?

Last year, friends came to me twice wondering if their friends had gotten good deals, maybe incredible deals, on art. One bought a Salvador Dali, and the other bought a Marc Chagall. You probably know these artists. They’re giants in the Western canon.

Both buys were purely financial investments. The Chagall was from a dealer. The Dali was from someone who’d inherited it. Neither buyer knew anything about art. Since both artists are household names, each thought they’d bought way below market. They paid thousands but thought they’d gotten paintings worth hundreds of thousands.

Both actually bought prints and paid above retail. The Dali was selling online for $200. If these buyers had been investing in themselves, they would’ve been thrilled to wake up to masterworks for the rest of their lives. Instead, they were really disappointed.

What happened? They mistook prints for paintings. At first, that’s a really easy mistake to make. Once you understand the difference, though, it’s just as easy to tell them apart.

What is a print? Prints are made by carving, cutting, etching, or adhering materials to a plate, block, or fabric. The plate, block, or fabric is then inked, and the ink is transferred onto paper using a printing press. Multi-colored prints are typically achieved through layers of printing from plates inked in each different color. (I’m leaving photography out of this for now.)

Like any medium, printmaking allows artists to achieve unique effects. It isn’t just a way to make multiple prints of the same image; although it’s most often used for that. Unique prints are called monotypes. Prints can also be less expensive reproductions of paintings and drawings—which is what tripped up my friends’ friends with the Dali and the Chagall.

People often confuse prints with drawings and paintings because they see the layers of ink on the surface of the print and assume that this texture is paint.

Why are prints generally more affordable than drawings and paintings? There are two main reasons—rarity and durability.

Whenever a work is unique, it represents more of the artist’s creativity and labor. Multiples, or editioned works, allow more of us to enjoy a single image made by the artist. That means the artist doesn’t have to put as much work into those pieces as they would if all of them were unique. That also means an editioned print isn’t as rare as a unique piece. In addition, there’s a vast difference in rarity between open edition prints (the artist could print as many as they want forever), big limited editions (200+), and small editions (≤20). Chagall, in particular, had a habit of printing massive editions.

Then there’s durability, which often impacts the condition of the work over time. One of the reasons paintings are so coveted is that canvas is way more durable than paper. If you tear a hole in canvas, it can be mended—sometimes seamlessly. Remember that kid who tripped at a museum and ripped a hole in a 17th-century Baroque masterpiece? That painting was restored. In comparison, if you tear a hole in a work on paper, you’re pretty much screwed.

Paper is also one of the least expensive materials. More durable materials are usually more expensive. A work on paper costs less for an artist to make than a bronze or a stretched canvas.

Here’s how to tell what’s a print:

1. Wide borders/Bleeds—Prints have to go through presses. So the sheet of paper is larger than the image printed on it, and the image often has a more definitive edge than other types of works (where the plate presses down to make the image). Some artists leave wide borders on their drawings, but they rarely do on paintings. A wide border and a harder edge aren’t definitive identifiers, but they’re clues. Word to the wise, the border of a print should never be cut off. Artists, that also means collectors have to frame the whole sheet. So, when you’re giving dimensions for prints, always give the sheet size, not just the size of the image.

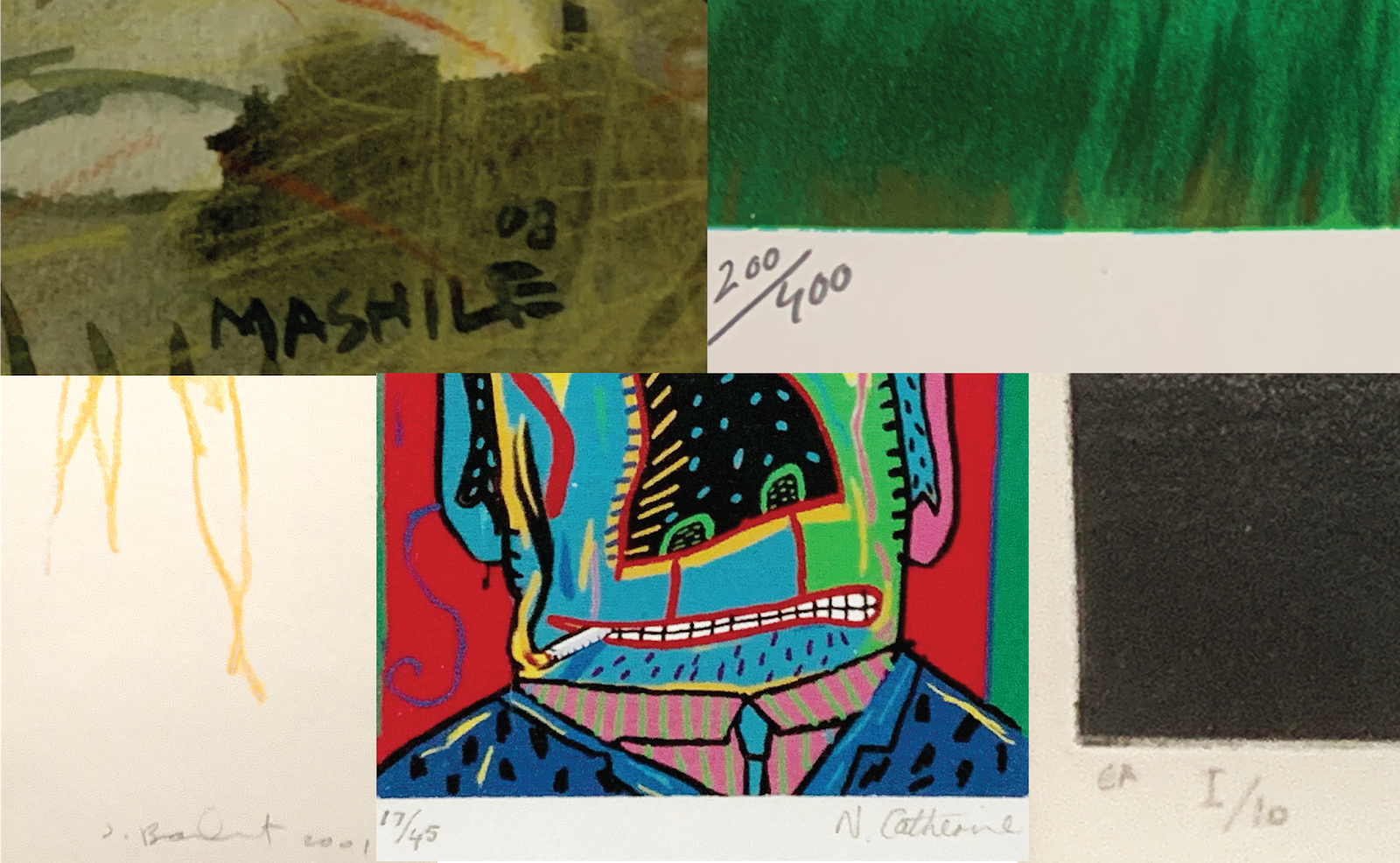

2. Texture—Compare the irregular texture of the yellow pastel drawing above with the regularity of the artist’s print (the one labeled EA). The more even/regular the texture, the more likely the work is to be a print. Like borders, texture isn’t definitive. Some paintings are so smooth and some drawings are so dense that they look like prints.

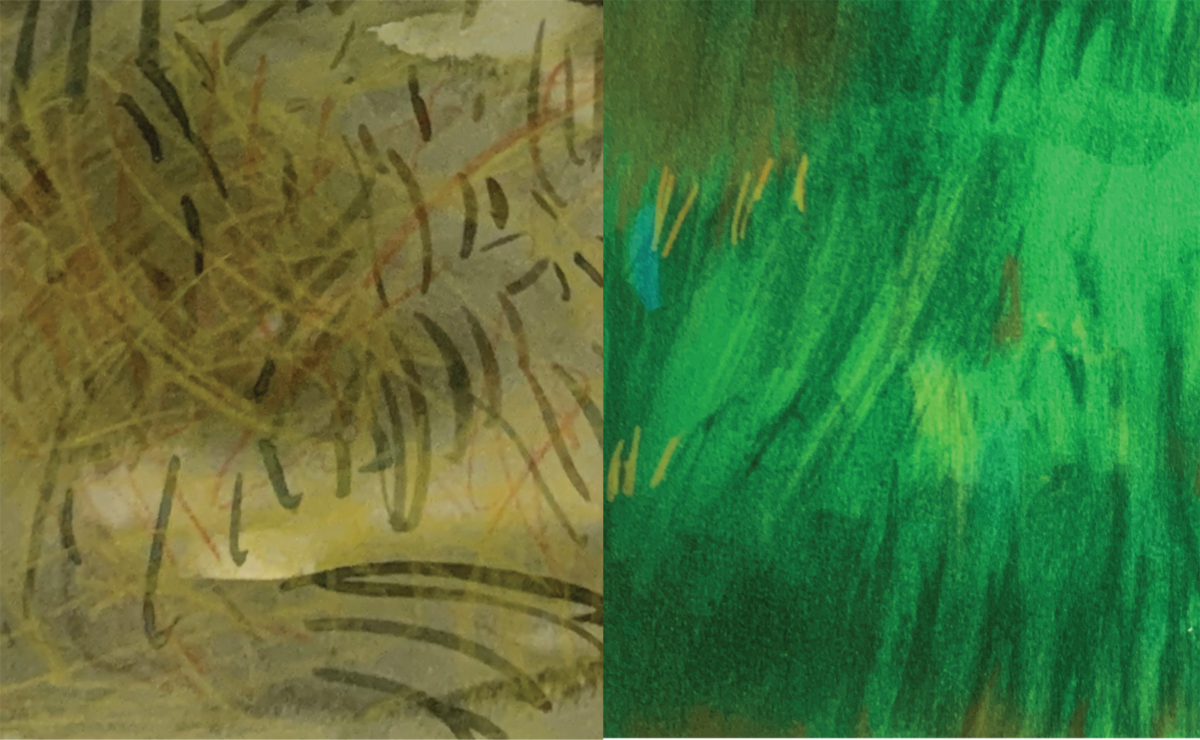

3. Signatures—I’ve never seen a signature on a painting that wasn’t painted as well. Painters also typically overpaint their signatures on the image. (Check out the painted signature on the Mashile.) Signatures on prints are normally in pencil on the bottom border of the print. Signatures on drawings are a bit tougher to distinguish because they, too, are often in pencil.

4. Edition Numbers—Edition numbers definitively identify a work as a print. On Western works, they’re usually on the bottom left of the print, while the signature is on the bottom right. (Eastern works are a whole other ballgame.) The first number is the work number. The second is the size of the edition. In other words, the Norman Catherine above is #17 of an edition of 45 (i.e., 17/45).

5. Artist Prints—If a work is labeled with AP (or EA “épreuve d’artiste” and a couple other iterations), it’s an Artist Print. Prints are usually made collaboratively by an artist and a printer. The artist makes the image, and the printer makes the prints. To be sure that the prints are what the artist intended, the printer will usually make one (an Artist Print) for the artist to approve before making the rest. If the artist is happy, the print run will go ahead with only one proof. If the artist isn’t happy, the printer will make revisions and another print for the artist to proof. Usually, it only takes 1-2 proofs for the artist to be happy. Then the printer runs the actual edition. Artist Prints aren’t counted in the edition size.

Any reputable dealer won’t conceal print numbers from you. The Chagall referenced above was clearly labeled with edition numbers, but it was also labeled as an original. That’s legitimate. A print is an original work by the artist, but it can be misleading. First-time buyers see “original’ and often think it means “unique”.

If you’re looking at a work and you’re not sure what it is, here’s your new best friends for figuring it out.

Google image search is like having Antiques Roadshow in your pocket. Take a photo of the work with your phone. Go to Google images. Click the camera icon, and upload the photo. If the work is by an artist with any established market, Google will tell you the name of the work and the artist. Plus, you also might learn how much the work’s selling for elsewhere. That’s how I found out that the Dali print was currently valued at only $200. Literally, it took me less than a minute.

Also research anything you see written on or about the work—either on the border, in the description, or on the label. Look them up in my fav fingertip guides for decoding printmaking terminology:

- The International Print Center of New York, IPCNY’s glossary of printmaking terms

- The Philadelphia Print Shop’s glossary of printmaking nomenclature and abbreviations

You’ve now got everything you need to tell a print from a painting. So go get some art!

Holly Hager is an art collector and the founder of Curatious. Previously an author and a professor, she now dedicates herself full-time to help artists make a living from their art by making the joys of art more accessible to everyone.