While older generations debate whether millennials are spending too much money on avocado toast, we at Art Zealous wonder: are young people spending enough money on art? As the callous facade of the art-dealing world fades and an influx of diverse sales platforms broadens the market, the idea of becoming an art collector is now more within reach for younger generations than ever before.

The growing demand for an online art market and the subsequent rise of online auction houses and artistic social media accounts has resulted in an online art industry valued at $3.75 billion, a number that is expected to triple by 2021. Surprisingly, however, these sales account for less than 10% of an estimated $45 billion in global auction and private sales. However small this market may seem, it represents the purchases of an important demographic for the future of art trading: millennial collectors. Much of the current concern of the art world, including that of large auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s, is shaping not just the online market but the overall art industry to appeal to young, up-and-coming collectors.

What exactly appeals to the younger generations of art collectors, and why are they buying the art they’re buying? To get the facts straight from the source, we interviewed a premiere gallerist, an executive at New Art Dealers Alliance, and a specialist from Christie’s whose personal experiences shed light on what it takes to be a young art collector.

When we hear the words “art collector,” most of us probably still think of multi-million dollar bids on French Impressionist works. Scott Ogden, however, is living proof that the stereotypically broke college kid can find creative ways to collect art on a budget. Ogden has eked out a collection piece by piece since his college years, acquiring such an array of ‘outsider art’ that he founded his own gallery here in New York. Located in Chinatown, Ogden’s Shrine Gallery exhibits many of the finest pieces of contemporary American Folk Art.

After a tour of his extensive personal collection, Mr. Ogden told us about his path as an artist, filmmaker, and skateboarder. He narrates a story about how a few, sporadic purchases by a small town college student evolved into a New York gallery overflowing with some of the most important artistic contributions to contemporary American culture.

Art Zealous: What was the impetus for starting your collection? Did you know that you were starting a collection when you purchased your first work?

Scott Ogden: I did not know I was going to start collecting. I was getting my BFA at the University of Texas, Austin, and a couple of things happened during the same semester: I stumbled into a lunchtime lecture on Texas prison art, which had some incredible artists like Frank Jones and Henry Ray Clark, that are sort of ‘outsider.’ Frank Jones is actually quite well known now, but these were Texas artists who were imprisoned, making incredibly unique work. I sat through this lecture and thought, “That was eye-opening and strange. What was that?” Then, I had a drawing teacher, I wish I remembered his name, but he was a visiting artist for a drawing class, and I was doing these sort of obsessive, strange drawings. He told me, “You’ve got to go down to this gallery in Waxahachie, Texas to see this folk art.” It actually took me a few months to get down there, but I finally made my way to the Webb Gallery, and you know those kind of experiences where you’re kind of like, “Mind blown.” I saw this art, and the Webbs came out and started talking about what I was looking at, all these artists had these unique stories—Bolden, Prophet Royal Robinson, Ike Morgan—and I got obsessed. I started going back whenever I could. I remember seeing Ike Morgan’s work and thinking, “This is so cool!” His work was torn up and ripped because he was hiding his art under his bed. He was in a state hospital in Austin. It was a situation where he was becoming an artist, and he probably wasn’t even aware of what he was doing, just creating obsessively and hiding things under his bed. Eventually an orderly took note and started saving things.

I just knew that piece resonated with me for some reason; I was very drawn to it. As a college student, I was, like everyone else, totally broke, so they worked out a deal where, I think it was like $150 at that time, which was so much for me, but I somehow managed it. From there I started helping the Webbs out: they’d go on a buying trip to visit an artist, or maybe just a recreational trip to Europe, and I’d stay at the gallery, open up on the weekends, watch the dogs; and in return they’d feed me while I was there, leave some beer, and give me a piece of art. I got my first Royal Robertson that way, from watching the gallery, and just kept doing that, slowly getting art. By the time I was graduating, I had somehow amassed a fairly good collection; much smaller than it is today, but a good collection. I went to Skowhegan, an artist residency in Maine, and after that I came to New York and got my MFA at Queens College. I lived in Flushing because that’s where Queens College was. It was really affordable. I started using my student loan money to buy art. I even bought some Prophet Royal Robertson signs at auction. Every semester I would buy something. I just never stopped. I’m still paying off my student loans.

AZ: Tell us about Shrine’s beginnings. What led you to start your gallery?

SO: As an artist, I’ve always made my own work, but I was also supporting myself as a high-end art installer here in the city for over a decade. If I was tight on money, or I was looking for something in particular, I would occasionally flip something, just to help get by. That’s when I started selling work and meeting a few collectors. I went to all the outsider art fairs, and I’d read all the books and magazines, so I knew a lot of the people involved in the outsider art world. I’d meet people who I knew were looking for certain things. I was actually looking for an art studio when I came across a listing on Listings Project. I came across this listing for a lower-east-side gallery, and the price was shockingly within reach. It took about 4 or 5 months of back and forth, but I finally was able to take the space. That’s how Shrine started.

AZ: We enjoyed your documentary, Make, which reveals some of your relationship with outsider art. Could you tell us a bit about your filmmaking?

SO: During grad school I got involved in a mixed-multimedia class where you couldn’t do what you normally did. I decided to do a video for which I would I create a folk artist, and I’d film a friend making all this fake folk art. My teacher said to me, “That’s okay, but don’t you know some of the real artists in this field? Why don’t you just go film one of them?” I thought that was a much easier idea, so I visited Ike Morgan and started filming with him, not knowing that it would become a documentary project. I slowly started filming artists when I visited them or searching out archival footage, but I wasn’t intentionally working toward a feature-length film. Then a friend came over, Malcolm Hearn, who helped direct and edit Make, and he told me, “This could be a feature. These artists sort of tie in together loosely, we could find the parallels if we work hard.” Thus, much of my time in grad school was spent documenting this world of outsider art.

AZ: You’ve mentioned buying art on eBay in the early years. Do you continue to do anything regarding shopping for art online?

SO: I always keep my eye on eBay still. There are still many live auctioneers, and there are always some interesting auctions. Live auctioneers host multiple companies’ auctions, so I keep my eye on things and see if there’s Americana or self-taught artists in the mix. I don’t collect as much as I was because I’m trying to put most of my resources and energy to keep this gallery moving. If I see something special that’s going undervalue, I wouldn’t mind trying to pick it up and either live with it or find it a home.

AZ: Do you think young collectors are shopping online for art or do they still want that in-person visceral experience?

SO: I do see a lot of young people coming to Shrine, walk-ins who happen upon my social media account or some who are just walking around Chinatown and find me. There’s a lot of young interest in my own gallery, and I would love to push that into collecting. A lot of people think collecting is outside their means, but really, if I could start doing it in college…There are clever ways to buy. It might not be a high-end object, but there’s a lot of affordable art out there that’s super underpriced. I never try to collect because it’s going to appreciate, but chances are, things usually do. Art is a relatively safe bet: you get to look at something wonderful, that you like; but it’s also a commodity. Having a gallery has reminded me that art is a commodity. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just what it is. There’s a ton of young energy. What I’d love to do is push that energy into starting to collect smaller, more affordable works.

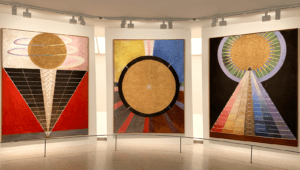

I also love social media so much, but what’s interesting with art is that there’s really no similar experience to seeing it in person. You can see a great photo on Instagram, but when you see it in person, it’s a totally different experience. That’s one of the things that I love about the art field: seeing Kyle Breitenbach in person is very different than seeing it 2 inches by 1 inch on your phone.

AZ: In your early years of collecting, what was the balance for you between financial and emotional motivations for purchasing a work?

SO: I think it was mostly emotional at that time. The financial end of it was, “How do I make this work so I can acquire this piece?” I’d become obsessed with objects, or certain pieces, really; it just hits that sweet spot for you. At one point, there were some Prophet Royal Robertson signs that were way out of my price range, for example. I thought to myself, “I can pay this off over six months,” so I convinced my parents to lend me a little bit of money and just paid them off every month. I wasn’t thinking, “What is this going to be worth 10 years from now?” I was thinking, “What will this look like in my house?”

AZ: Do you think you’re the norm in that regard?

SO: There might be a mix, but the contemporary art world is inherently about art as commodity. I was starting off in this world of outsider, self-taught art, which was more of a heart-pull, something that really moved people and drew them in. The stories for people like those in Make are so interesting and are very much a part of their art; but also, for me, it has to visually hold up before the story makes any difference. If you don’t think a Bolden is visually interesting, then it doesn’t matter if he’s blind. I try to distance myself from the narrative when checking something out because I want it to hold up as a piece of art. Then, when you see the story and the work together, it enhances the relationship.

AZ: When you were searching for art online you wanted to buy, were these pieces you had had experience with in-person?

SO: I might have had a rough idea, but there are still surprises. You know, you get it and you think, “This is very different than I thought.” You know, much bigger, or in a different condition, or the colors are way off because someone photographed it poorly. eBay’s a gamble, but it’s kind of exciting in that way. Sometimes the piece is 20 times better than you thought it was going to be, so a little bit of both. I’ve bought things at auction, where it’s almost like online dating, and you’ve got this conception of who the person is or what the object is; then it shows up, and it’s very different, much smaller or larger. Things are always askew after you’ve just seen it in a photo.

AZ: From your interview with us last year, you mentioned some of the lesser-known Folk art auctions and fairs you were attending. What made those important to your experience and collecting? Do you have any advice on how to sort of break into that underground art fair scene, especially for people who have an interest in art, but aren’t necessarily associated with the art world in a professional capacity?

SO: What’s cool about it is that with the Internet, you can figure out all this stuff pretty quickly. I think it should be a bit of a search. My friends who started me off in this field, their gallery was in this small town, Waxahachie, Texas. It’s a destination. You’ll find the smaller auctions if you do a little sleuthing and looking around. There aren’t that many, but they’re not hiding them. One of my favorites is a gallery in Atlanta called Slotin, and they have some great stuff. On eBay you can still find some self-taught and contemporary artists. A foundation I work with founded by Bill Arnett called Souls Grown Deep is an amazing foundation in Atlanta, and Bill essentially drove the south obsessively through the mid 80s and early 90s, and he was meeting, discovering, and collecting work by southern, self-taught, black artists. He’s had a little controversy; I think people were annoyed: he was paying more per piece of art than most people who were going to be picking art from artists. But he was also collecting in bulk. He was trying to preserve the environments entirely when could, but it doesn’t work. You tell an artist you’ll pay them not to sell their art, but a lot of these artists don’t have any money, so when someone comes around offering them some money for something they made, it’s how you survive. But he collected a ton of art and now it’s part of this foundation. They’re giving out huge gifts to museums. The Metropolitan just took a huge gift, I think around 70 works, that’s going to result in a big show of southern self-taught black art at the Met. San Francisco MoMA just took a large partial gift, and it’s currently a show itself now of all this self-taught black art, which is getting integrated into their contemporary collection holdings.

AZ: We were interested in one specific part of the website for Shrine, where there are a slew of skateboard decks featured. Are you personally involved in the skate world?

SO: Yeah! I grew up skateboarding. That’s actually how I got into art. I remember going to a skate shop in our little suburb outside of Dallas with my mom when I was ten or eleven. I got to pick out my first board, and it was all about what it looked like. I was kind of a shy little nerdy kid, but there was something so intriguing about seeing all these decks that were much more punk rock and cool than anything I had ever seen before.

Around 2010, I decided to make a small company called Make Skateboards, and we mostly do artist editions with cool contemporary artists, like Erik Parker, Kenny Scharf, Jacob Kassay, but I also did one with the Adolf Wölfli Foundation in Switzerland. It’s been a little on the back burner since opening Shrine, but I actually just brought it all under the Shrine umbrella last week.

AZ: It seems that from an early age you were drawn to the independent art scene.

SO: Yeah, it’s true. In terms of collecting art by some of these contemporary artists, it’s a really good deal since most of the skateboards are $125. Eddie Martinez’ are a little bit more because it’s a smaller edition, but regarding collecting art, it’s interesting because they’re utilitarian objects to be skateboarded, to be used, but they’re also beautiful on the wall when installed right.

AZ: How do you think art collecting will change in the near future? What about the art market in general?

SO: I don’t know how collecting will change, though I’m hopeful as not just a gallerist, but also as someone who started fairly young trying to collect things. I hope the trend of younger people starting to realize they can actually collect things continues. It happens slowly, you know: you buy a piece of art once a year, and after a couple of years your home has a lot of original art in it. It seems daunting the first time you do it, like anything, especially when you’re spending money on something you don’t necessarily have to have and when you don’t have a lot of money. I still feel the same way when I buy art. Usually, theoretically, I can’t afford it, still. Something will call me, and I’m like, “I still have to have it.” So I hope more young people start thinking, “Wow, that’s $700, I could figure out a way to make that work.” A lot of people have careers in tech, and they maybe don’t think they have an art eye, but it’s not hard to find things you like if you start looking. But the art market in general, the art world in general, I don’t know. It’s a weird time. I keep reading articles about middle-tier galleries that have a large staff, large space and I’m sure a huge overhead, but they’re not at the level of some, like David Zwirner or Gagosian. It seems hard right now to stay afloat.

AZ: Do you find that there’s a difference between your search for artists to feature in your gallery and your personal tastes?

SO: I think they’re about the same. I probably can’t afford a lot of things I have in the gallery, and you can’t have everything you like, but I definitely try to bring that initial love for the art. Everyone’s got different tastes, but I try to use my taste to conceive shows. So far at every show I’ve had, there’s something I would have wanted to have, and that’s the way I want to continue to do it.

AZ: Do you have any further general advice for young, aspiring art collectors?

SO: I’d just say, go for it! Even if it seems like it’s going to crush your finances for the next few months, figure out a way to do it! There are all sorts of creative ways to save a little bit of money. I recently learned about Art Money, where they loan you money at very low interest, and you buy an art piece and pay it back over the course of a year. They take a small percentage, and they pay the gallery immediately. You’re able to buy art that you can’t afford at the moment, but you could, in theory, pay $110 a month for. I believe Art Space also has a sort of monthly payoff. So there are creative ways to do that. Also, just eBay, if you want to start small and find a couple things you like. Although, if you were to type in contemporary art or outsider art or self-taught art, you’re going to find a lot of stuff that’s not really art. You have to really dig. It’s better if you’re a bit more specific and already have a few artists you’re interested in.

AZ: What’s next for you?

SO: At Shrine in October, I will be opening a powerhouse painting show of new works by NYC artists, Mason Saltarrelli and Bill Saylor. The gallery will also be participating in the Paris Outsider Art Fair in late-October as well as NADA Miami in December, which will be my first ever trip to Miami oddly enough. I’m also working to find time for my own art making and starting a second documentary (a follow up to MAKE) on American self-taught/outsider artists, which I’m really excited about. The gallery will be launching some new artist skateboards soon too!

Images // Photography Alice Oh

Additional reporting by Peter Dreux