Every September, galleries mark their emergence from the slow summer months with enticing exhibitions, inviting collectors who have just returned from holiday back into the swing of things. This year, the excitement in Amsterdam is particularly palpable, as galleries emerge not only from the summer lull, but from months of lockdown, postponed exhibits, and limited gallery attendance. The city has eased regulations, enabling galleries to present their September exhibitions with considerable fanfare. Last weekend I attended several openings, applied numerous rounds of hand sanitizer, and took note of the discourse fueled by these statement-making September shows.

Among the galleries I visited, I noticed an emphasis on technology– not merely as a medium or a subject to reflect on, but as a conflation of the two. That the exhibiting artists hail from around the world suggests a global interest in the topic, but it’s still notable that several galleries– within a block radius of one another– would be drawn to artists exploring complementary themes.

Perhaps innovative applications of, and reflections on, various technologies, are well represented in Dutch galleries, because disciplinary borders are so porous here. In the Netherlands, contemporary art discourse bleeds into the fields of urban planning and green energy, communication and conflict resolution. In fact, ‘multispecies communication’ was the chosen subject for this year’s Dutch pavilion at the (now postponed) Venice Biennale. It seems that Dutch curators are drawn to artwork that provides insight into the fraught relationship between human beings and machines.

Galerie Caroline O’Breen

At Galerie Caroline O’Breen, the exhibition ‘Transatlántica’ explores a particularly tense aspect of this relationship: the role technology plays in extremist politics and the construction of national identity. ‘Transatlántica’ features recent work by Brazilian artist Elsa Leydier, including the series Brazil: System Error (#elenão), in which the artist manipulated images using text code taken from the lips of Brazil’s right-wing President, Jair Bolsonaro.

The series was created in 2018, during Bolsanaro’s presidential campaign, which was marked by repugnant comments about indigenous Brazilians, Afro-Brazilians, the LGBTQ+ community, women, and progressives. Similar to Trump’s twitter tactics, Bolsonaro’s campaign spread discriminatory views towards these groups through social media, particularly the messaging app, WhatsApp. And like Facebook, which has been rampant with fake and misleading news stories for the past few years, WhatsApp became a hotbed for misinformation, spread by Bolsonaro’s followers in dozens of private messaging groups.

As Leydier’s frustration with the candidate’s offensive tactics grew, she became fixated on what gallerist Caroline O’Breen calls, “the discordance between the-tropical-paradise cliché of Brazil and its corrupted failing power machine.” Leydier sought to raise awareness about the currents of racism, homophobia, and misogyny plaguing Brazil, which were so at odds with the image her country presented to the world– that of a blissful, tropical landscape of palm beaches, where football fans root on their favorite teams, and sequin-studded revelers dance in the streets during Carnival.

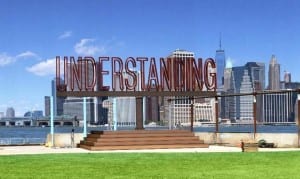

Leydier typed ‘Brazil’ into a search engine and selected the first photographs that appeared. Not surprisingly, these were images that reflected Brazil’s global image as a sunny, colorful, jubilant nation; pictures of tropical birds, the Amazon rainforest, and Carnival. Into their text code, the artist inserted direct quotes from Bolsonaro’s most violent statements about Brazilian minority groups. This digital alteration caused the images to glitch, affecting the structure and color of their pixels. In many, a kind of ‘sliding effect’ occurred, causing a rectangular section of the photograph to shift an inch or two to the right. In pictures of birds and people, such as Garotos de programa and Petralhada, the effect is eerie; faces are split down the middle, their noses and wings symbolically amputated. By stimulating such dismemberment using Bolsonaro’s own, loathsome words, the artist makes visible the very real, very physical ramifications of the President’s violent rhetoric.

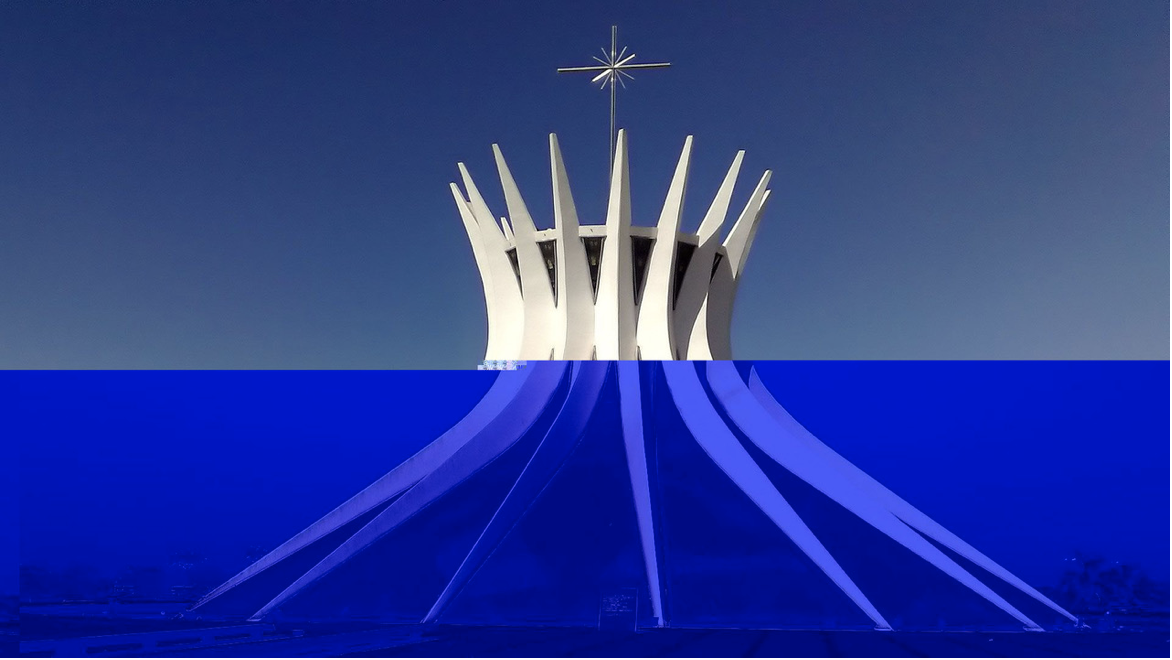

In other manipulations, rectangular zones are tinged a fluorescent hue that contrasts the natural lighting in the rest of the photograph. These sectors read like infrared footage of an environment, as if the camera has captured what lies beneath the surface of the original image. Such works, like Un centimetro de terra, are less violent but more foreboding than their severed counterparts. One gets the sense that Leydier is using Bolsonaro’s language not as a weapon, but as a tool to look deeper; to discover the truth embedded within the pristine, tourist-friendly image Brazil projects to the world. An indigo filter transforms the building at the center of Un centimetro de terra into a tentacled creature not unlike the monster from Netflix’s ‘Stranger Things.’ And like the upside-down reality that monster inhabits, this world is filled with a thick haze that obscures the dark forms in the distance.

At Galerie Caroline O’Breen, Garotos de programa, Petralhada, and Un centimetro de terra are all exhibited within imitation smartphones: lightboxes made from wood and glass. The display comments on the use of social media, and the internet in general, to construct and disseminate a uniform image of what Brazil is. Though I find the works have a stronger visual impact on a larger screen– and would be curious to see enlarged prints of each– the choice suits the narrative Leydier is telling with this series. It engages viewers by alerting them to their role in the spread of (mis)information, and in the replication or subversion of cultural stereotypes. Ultimately, this reminder of the masses’ autonomy and influence reads as an almost-Marxian call to action, which makes for a dynamic dialogue between President, Artist, and Viewer, all on a series of 5-inch screens.

Stay tuned for Chloe’s next review in this series highlighting technology and art in contemporary Dutch galleries.

Figure 1: Elsa Leydier, Garotos de programa, from the series Brazil: System Error (#elenão) | 2018 Wooden LED light box, museum glass, via Galerie Caroline O’Breen

Figure 2: Elsa Leydier, Petralhada, from the series Brazil: System Error (#elenão) | 2018 Wooden LED light box, museum glass, via Galerie Caroline O’Breen

Figure 3: Elsa Leydier, Un centimetro de terra, from the series Brazil: System Error (#elenão) | 2018 Wooden LED light box, museum glass, via Galerie Caroline O’Breen