above image // These fabulous prints, Japonisme and The Azurite by Ruth Marten, are the best of both worlds. Marten uses proof impressions (partial prints) from the 18th to 19th centuries and completes them with her 21st-century vision. Courtesy C.G. Boerner Gallery.

In my recent column about prints, it might have seemed like I was casting serious shade on them. On the contrary, prints are wonderful—especially when you understand them, but they’re a bit of a dichotomy. For collectors, prints tend to be either an entry point or a passion. New collectors often start with prints because it’s more affordable to buy editioned works from well-known artists.

When I started collecting seriously, prints seemed a lot less scary than other original works. They only “seemed” a lot less scary because I didn’t understand them. Like many novices, I thought of prints only as a way to make multiple copies of the same image.

Few collectors take prints to the next level. In printmaking, there are myriad techniques, all which allow artists to make images with unique qualities. The learning curve is huge. Most of us have heard of silkscreens (aka serigraphs), but there are aquatints, chine collés, engravings, lithographs, woodcuts, and lots more. Serious print collectors have to dig deep to grasp all the nuances.

What can artists do in prints that they can’t do in paintings or drawings? The biggest advantage of printmaking for the artist isn’t reproducing the same image. It’s that they can manipulate the ink on the printing plate in a way that can’t be done in other media. Once an artist marks a porous surface (like canvas or paper) with liquid pigment, that mark can’t be removed without leaving traces.

In printmaking, the artist forms an image on a much less porous surface—like wood, metal, or stone. They make the image with techniques like carving, etching, or scratching. Then the ink is applied to the plate. While it’s wet, the artist can brush, scrape, or change it without leaving any traces of pigment on the final surface.

I asked Armin Kunz, a New York gallerist who specializes in prints, why he’s so fond of them. “The black box is what’s so magical about prints. You never know how they’re going to turn out.”

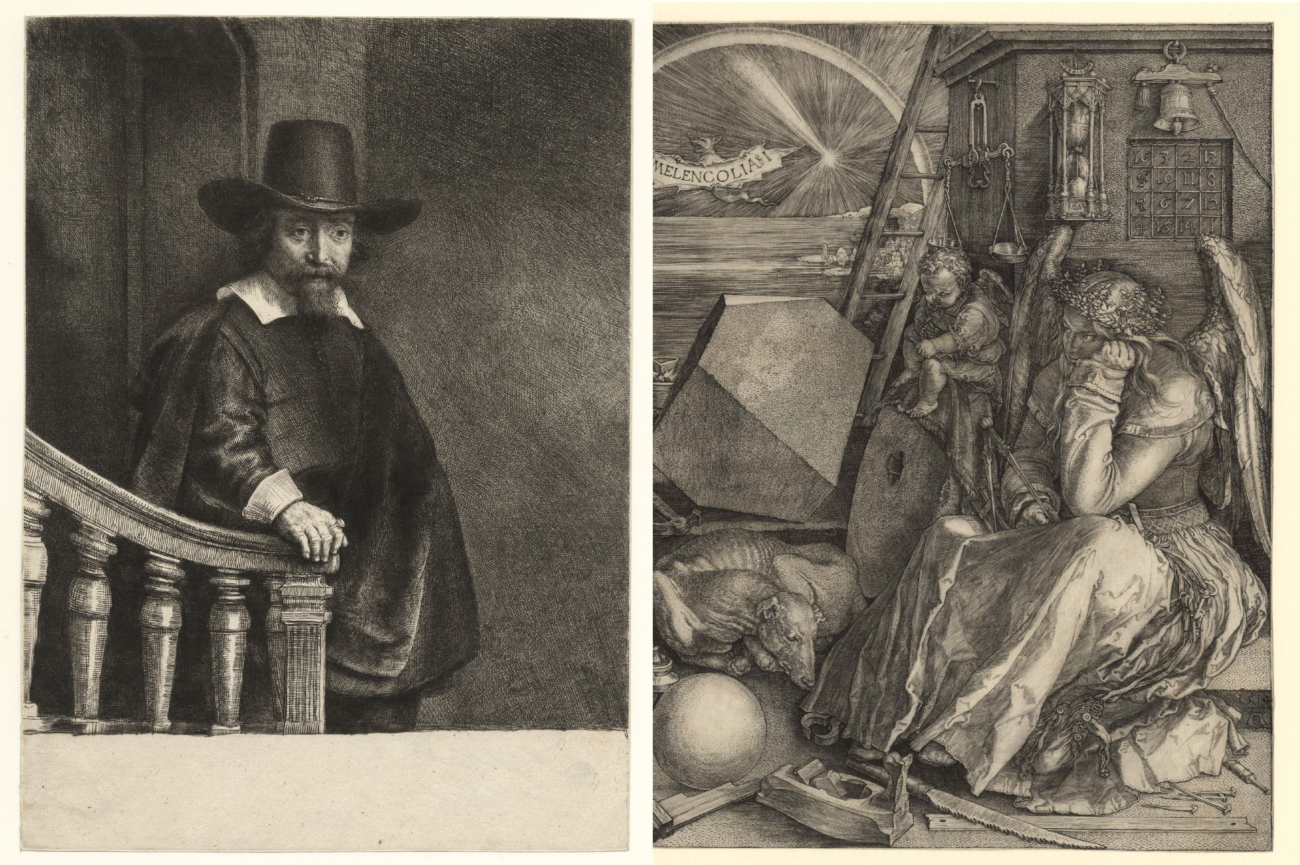

These prints, Ephraim Bonus, Jewish Physician by Rembrandt and Melencolia I by Albrecht Dürer are exceptionally excellent works—not just because of the talent of the artists but also because of the craft of their printmakers. Courtesy C.G. Boerner Gallery.

How has printmaking changed? Printmaking has been around for centuries—about 600 years in the West and 1,600 in the East. The concept of a “limited” edition only showed up in the late 1800s. Before that, it was the physical limitations of the materials themselves that determined how many prints were made from one image.

With some printmaking techniques, the materials degrade quickly. In drypoint, my personal fav, the image is engraved onto the plate with a very hard stylus that creates a burr on the edges of the lines. That burr holds a lot more ink than the rest of the plate and creates the gorgeous, velvety texture you can see in the Rembrandt above, but the burr gets worn off really quickly by the pressure of the plate. So this Rembrandt has to be one of the earliest impressions of that particular image.

Traditionally, copper plates were used in printing. Now even plexiglass is common, but Kunz believes that technology isn’t what changed the mainstream perception of prints as just a medium for multiples. “Pop art was the difference. There was a paradigmatic shift in the 1960s with Pop Art where the print looks substantially like the painting.”

So how can you tell a $1,000 print from a $1million print? Kunz says, “It’s all about the quality of the impression and the materials.”

Faithfulness as passion for property, a contemporary print by Dasha Shiskin. Courtesy C.G. Boerner Gallery.

What do you need to know about taking care of works on paper? Works on paper might be more affordable, but that’s because they’re also less durable than other materials. Moisture of any kind can damage them. So don’t be hanging prints in your bathroom, and think twice about them long-term in the tropics.

Sunlight can also take a huge toll on prints, and color ink is more susceptible than black, but you can easily prevent sun damage by framing them with UV plexiglass.

Discoloration of the paper can also be an issue. If you’re matting a print, make sure your mats are acid-free, and just say no to any kind of tape.

Finally, paper can be torn or sliced fairly easily, so always frame your prints in plexiglass, never in glass. Not even museum glass. If the work gets dropped, the plexi might crack, but it won’t shatter and cut your print into ribbons.

This is one time when age is apparently a plus. Kunz assured me that, “The older prints are, the sturdier they are.”

Old or new, prints are one of the most affordable ways to bring art into your life. If you’re in New York this week, check out Art on Paper. It’s a lovely fair for prints as well as for all kinds of other works on paper. I’ll be walking the fair on Friday, and Armin will be in his booth all fair long!

Holly Hager is an art collector and the founder of Curatious. Previously an author and a professor, she now dedicates herself full-time to help artists make a living from their art by making the joys of art more accessible to everyone.