Wall of the Winds by Gunjan Tyagi is a wonderful example of fine art photography. The image is arresting, capturing the drama of an Icelandic landscape. But what makes it fine art is the wall crushing the people who’ve built it. Image courtesy the artist.

These days, even I can take a decent photograph—and that’s a miracle. Regardless, I’m far from being an artist. Exponentially better technology has just nearly idiot-proofed photography. Creating an image is completely different than it was even 10 years ago. The proliferation of images in global culture bears witness to that. With technology upping everybody’s photography game, how do you tell fine art photography from all the other snaps?

The rest of us take photographs; artists make them. All of the images here are good examples of the elements that elevate a photo into fine art—and that doesn’t necessarily have to do with producing them on expensive paper or limiting how many are printed.

The most important element is the gut punch. Art critic, Carter Ratcliff, recently defined art as something that communicates “inexhaustible meaning.” (Check out his brilliant lecture about art and the Trump era.) His definition is a little narrow for me—I think only masterpieces communicate inexhaustible meaning. My definition of art is more inclusive; it has to communicate something profound, but I love his distinction between art and “non-art.” If a photo is just cool or aesthetically pleasing, then it’s non-art for sure. For instance, a photo of a beautiful sunset is just a beautiful photo (aka non-art). Trevor Paglen’s photo of a beautiful sunset, with a deadly Reaper Drone hiding in its depths, is art.

If you don’t care about collecting fine art and just want to surround yourself with cool photography, go on with your bad self, but spend accordingly. I get morally outraged when someone spends $20,000 on a piece of non-art. It burns me up for two reasons. First, the overpayment could have supported actual artists. Second, if the art-fair crack wears off and the would-be collector realizes he’s been taken, it might sour him on art collecting for good.

Here are the gut punches in three very different fine art photos. Wall of the Winds by Gunjan Tyagi (above) is probably the easiest to identify. The image isn’t just interesting, it documents a performance. (See my earlier column about how photography often memorializes performance art.) Tyagi uses whimsy to broach the profound. In this work, she’s trained her artistic lens on our current obsession with wall-building. The image can be read in multiple ways. The wall is dwarfed by the immensity of the landscape. The wall is hideous in comparison to the natural beauty that it mars. The builders seem to recognize the futility of their task. And my fav, the builders are literally being crushed by their attempt to protect themselves. Maybe not quite inexhaustible meaning, but I could go on….

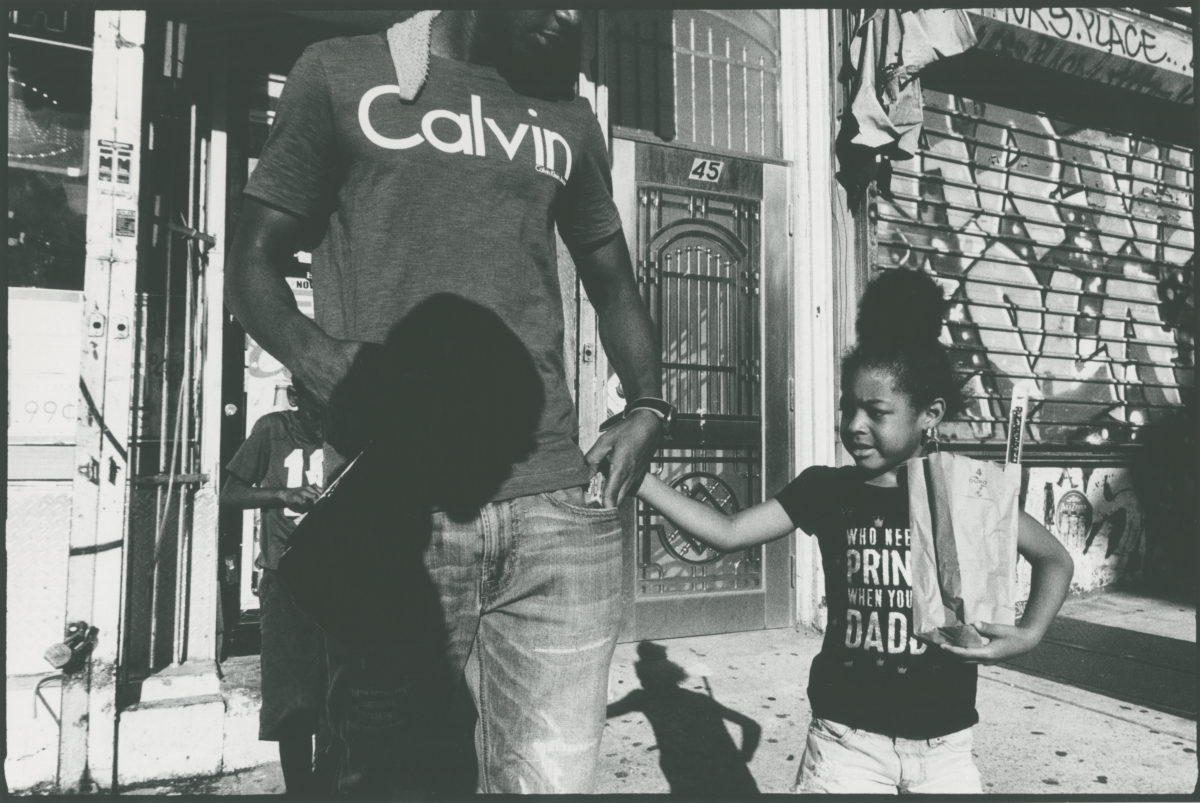

Laurent Chevalier’s Untitled (father’s hand) might be a bit more difficult to peg. Since we see the world in color, our lived experience is necessarily distanced a notch from a black-and-white image. Working in black and white instills the image with a level of abstraction, but rendering an image in black and white doesn’t guarantee that it’ll be art. So what elevates this image from simple documentation to fine art? It’s the distillation of the complexity of the father/daughter relationship into a single instant. Chevalier cropped the image to intensify the tenderness in the father’s gaze—which we don’t even actually see. The girl’s excruciating focus on her father’s hand in the urban cacophony. The potentially ominous shadows. The interplay of the words on their t-shirts. The heightened presence of a black father when we know that, in underserved neighborhoods like the one pictured, so many are absent.

Jassy by Jason Derek North is a completely different visual adventure. His practice unleashes the power of environments that allow us to shed our inhibitions. Rather than removing color, North abstracted this figure into electrifying hues. Focusing on the movement of his subject, he captured the energy of the moment in a seductive visual language that recurs throughout his work. This image can be read as either ethereal or exuberant. More importantly, North turns his experience of historically marginalized queer culture into universal representations of the human spirit breaking gloriously free. How’s that for profound?

What are the other elements of fine art photography? Another must is limited production. Art is about the rare and handmade. Perhaps no other medium is now produced en masse as much as the photograph. It’s ubiquitous. So artists always limit their production. With other media, an artist’s production can be restricted by physical limitations. The artist literally can’t produce more than a certain number of pieces per year. Since photography isn’t subject to such constraints, however, artists who work in the medium create artificial rarity by limiting how many works they produce. Photographs, like sculpture, are often produced in multiple sizes. So the artist might make the same work in three different sizes, each in editions of three (for nine total). Or they might make only one size in an edition of ten. Don’t just take the edition size on its face. Ask if the image is made in multiple sizes, too.

For artists, one of the wonderful things about working in photography is that they can exhibit their work, determine the edition size, but then only print the works on demand. That allows artists to offer more works without having to lay out all the cash upfront to produce the entire edition and then store the multiples until they all sell. It also means you might get the bonus of having a work that ends up being in a smaller edition than what you originally bargained for.

As for production, that’s important, too. Fine art photography is generally produced on high-quality materials via high-quality techniques, but not always. Some artists incorporate the rarity of unique Polaroids into their practices.

Finally, a word about pricing. Unlike other works, the cost of photography can escalate incrementally as an edition sells. So be the first to believe in a work enough to buy, and you can get the best deal.

Holly Hager is an art collector and the founder of Curatious. Previously an author and a professor, she now dedicates herself full-time to help artists make a living from their art by making the joys of art more accessible to everyone.