What makes surrealist works so deeply intriguing and (dare we say) sexy? It’s all in the lighting. Our resident astrologer Cristina Farella of Eighth House Astrology digs into the light and shadow of paintings by Giorgio de Chirico and Remedios Varo, two surrealists known for their haunting works.

If you take a walk before sunset, you’ll notice the architecture in your environment seems to grow long. Shadow as geometric shape slips out from under windowsills and porticos. Ivy-covered walls are obscured in slanted darkness, and edges of lawns seem to drop off into black. The feeling is eerie, somewhat dreamlike. This is the light that precedes the more jubilant light of sunset, which has been immortalized in shades of pink and gold for centuries. This pre-sunset light holds a stranger tone, somewhat uncomfortable to the eye.

As the Sun moves through the sky each day, the light changes on a continual basis. We are so accustomed to this marvel of shifting light, that the arc of the Sun through sky is one of the most mundane parts of experiencing a day. Each morning the Sun rises, leaps toward noon, and then descends back toward its setting point.

The Impressionists made an entire style of art around the engagement of light, though we can reach much further back into history and observe that artists have always employed light as a way of establishing mood in a composition.

Translation of Astrological Light

The Sun in astrology plays the pivotal role of lighting up a particular house of a natal chart, its golden light suffusing a particular sector of reality with “self-identity-ego.” Astrology however is not simply the study of static natal charts. Each and every moment of every day, the planets and luminaries are in transit, moving through our sky invisibly during the day, and visibly at night.

The Sun’s path from daybreak to dusk is what causes these aforementioned changes in light, and as the Sun moves through the sky every day, he occupies astrological houses 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, and 7. There are also sometimes softly glowing suggestions of light while the Sun is in House 2, prior to dawn, and sometimes House 6, just after sunset.

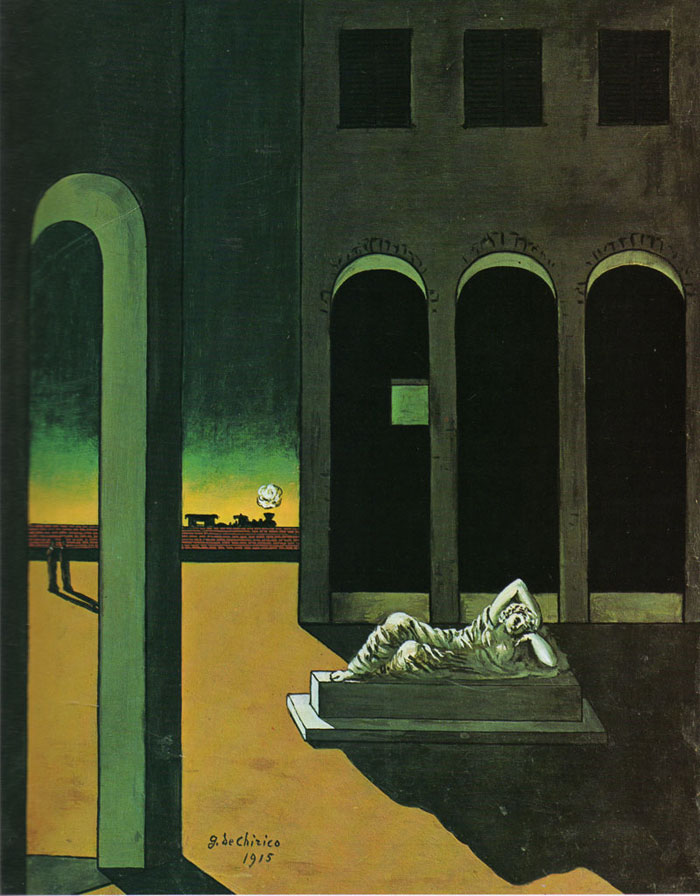

And so on a recent walk through my neighborhood before dusk, I noticed that buildings I normally see at noon suddenly resembled something from a de Chirico painting—slanted, mysterious, stark against a curiously lit sky. At this time, the Sun was in the 8th House, a place which ancient astrologers considered a locus of death and destruction.

Modernist surrealist painters used the light of the astrological 12th and 8th Houses, and the non-light of the 4th House, to achieve strange and dreamlike works, rendering the light of dawn, pre-sunset, or the dark of darkest night.

The 12th, 8th, and 4th Houses are discrete areas of an astrological chart, but are all linked by virtue of being places of the unconscious, dream states, nightmares, the deeply psychological, all archetypal areas of human imagination. These are indeed the places from which surrealists claimed to draw their inspiration, Andre Breton writing in his “Manifesto,”

I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak…Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life.

What follows will be an examination of the qualities of light in surrealistic painting, in relation to the light used by the artist. Looking at works by Giorgio de Chirico and Remedios Varo, I will show the connection between light in surrealist art and the astrological houses, and shall argue that to understand light from an astrological perspective deepens our sense of what the painting conveys psychically, magically, and emotionally.

Discomfort, Suspicion, Dream: the Light of the 8th House

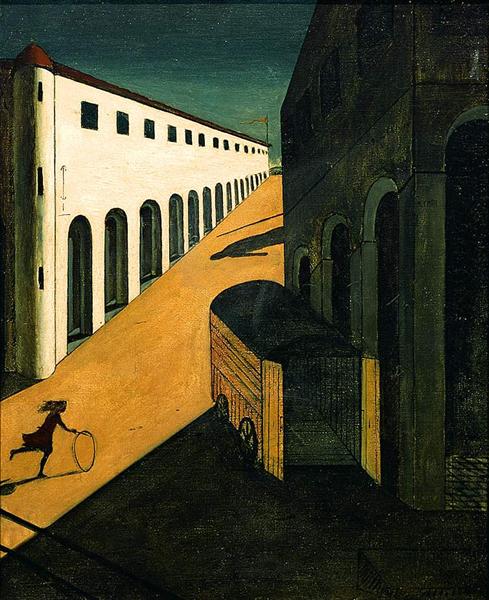

When the Sun is in the 8th House, approximately two hours before sunset, the world is cast in slanting light, distorting windows and buildings, throwing long and strange shadows out from under us. Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings are the quintessential representation of this time of day, with the interplay of light and dark, long shadows casting their own geometrical interventions into the composition.

What’s even more emblematic of the 8th House in these paintings, though, is the quality of the light and the mood it creates in his paintings. Loneliness, a sense of isolation or abandonment, qualities of a dream that might soon slip into a nightmare, unnamed villains peeking out from around porticos—these are all feelings we experience when looking at his Italian squares.

De Chirico’s painting Ariadne (1913) is a wonderful example of this, and the reference to the myth of Ariadne, a woman trapped in the minotaur’s labyrinth, is also related to the 8th House, which relates us to themes of entrapment, overwhelming trauma, and threats of violence.

If the astrological 8th House governs the tragic, taboo areas of life, then its compatriot is the astrological 12th House, which acts as a haunted catch-all for experiences of escapism and dissolution, the ineffable, a sort of Dionysian portal into dream and death.

The light while the Sun is in the 12th House glows gently, as the Sun is at this point over the horizon, slowly illuminating the day after a dark night. This is a moment of liminality, Sun not fully illuminating the world, but casting a soft and gentle light over the world.

In de Chirico’s paintings, there is a sense of whimsy and sadness, an echoing suggestion that the scene depicted is of some intermittent stop along the road to the afterlife. Small figures may present themselves on the edge of a composition, as in Italian Square (1915), but they are out of reach, whispering to one another, ignoring us, the spectator.

His work Melancholy and Mystery of a Street (1914) too seems like an excerpted image from a dream, as we seem to view a city street from an elevated, floating vantage point, as a young girl in shadow runs with a wicker hoop. Around the corner of a building looms the shadow of a man, perhaps threatening to the young girl, ominous in character. The white building on the left-hand side of the painting is dotted with identical porticos and windows, suggesting that they extend into eternity, like a building in a dream.

The light in both of these paintings, as well as many others of de Chirico’s square series, seems to hover somewhere between dawn and darkness. The light, the loneliness, and the expanding yet desolate environments are reminiscent of the echoing and strange world of the astrological 12th House, where one can find themselves confined to experiences of illness, escapism through drugs or other dissociative states.

In his “Manifesto,” Breton writes, “Apollinaire asserted that Chirico’s first paintings were done under the influence of cenesthesic disorders (migraines, colics, etc.),” a fleeting but fitting connection to the realm of art that emanates from the 12th House.

Transmissions from the Womb: the Light of the 4th House

The astrological 12th and 8th Houses are indeed places of surreality, taboo, and dream, but they hover together above the horizon line. They are complemented by a third house below the horizon line, the 4th House of the astrological chart. Here, there is no light, the Sun has set and we are in the small hours after midnight.

The 4th House in astrology is associated with themes of feminine generation, the womb, connections to the mother, our ancestry, places we emanate from. It is the “lowest” part of the natal chart (though it is the most northern), and here we find connections to rooted, creative, and deeply intuitive themes.

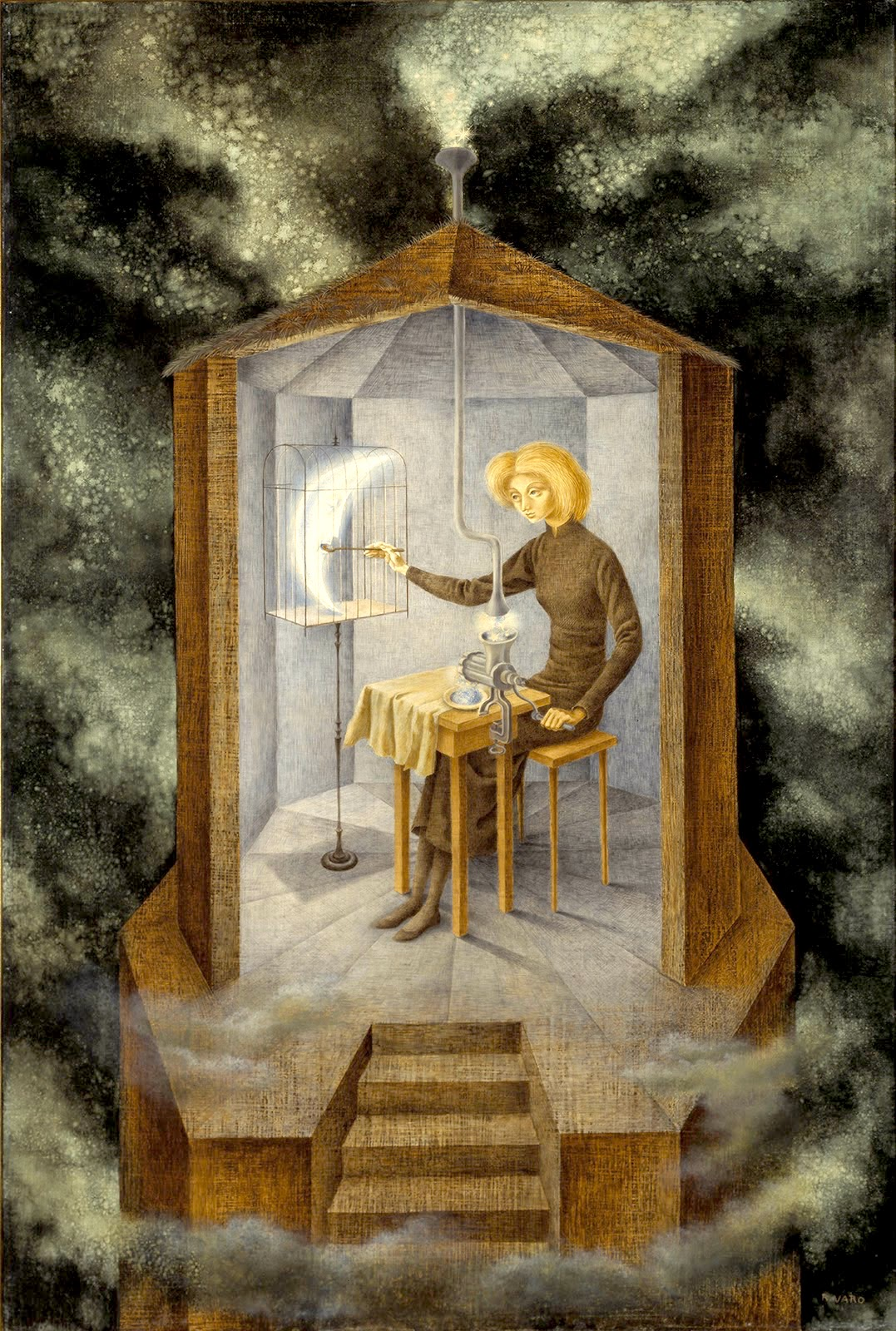

Remedios Varo’s paintings can be identified as art which emanates from the 4th House. Unlike the scenes depicted by de Chirico, Varo’s work almost always takes place in a dark environment, places where there is no visible light in the sky. The Moon and stars are more readily featured in these compositions, even becoming characters in these lyrical scenes.

Varo’s Papila Estelar (1958) seems to take place in the depth of fantasy or dream, a woman feeding a small Moon in the dark of night. Her painting Troubadour too shows figures moving through a dark enchanted wood, a fertile space seemingly underground, or in the dark of night, filled with fairytale creatures—all reminiscent of the energies of the 4th House.

Looking at a vast array of any work by Varo shows a preponderance of nighttime or subterranean landscapes, which is part of the reason why her work is so deeply evocative of surrealistic dream narratives. Looking to her natal chart, too, we see that her natal Mercury and Sun sit in Sagittarius in House 4!

Her Mercury is eminent, as it is the ruler of her midheaven, ascendant, and North Node. It’s also the dispositor of her natal Venus and Jupiter, benefics focused on the cultivation of art and pleasure. The deeply feminine themes of Varo’s works also help us categorize them as belonging to the 4th House, the place of ancestral secrets.

Though this essay has focused on the work of two painters, my intention has been to draw attention to the use of light to convey a particular mood in paintings, in turn connecting this light to that of the astrological houses associated with dream, taboo, surreality, and escape. The present theory can be applied to any work of art one comes across which seems to prominently showcase light with deliberateness.

Indeed some works of surrealism seem to take place in broad daylight. Consider Max Ernst’s The Spanish Physician. A wildly fantastical image of a horse and two figures, as though dripping with blood, feather, and muscle, in the stark light of day—the astrological 10th House, where there is no shadow at all. The Sun reaches this house each day at noon.

This complement to House 4, which is to say, its opposite, represents one’s public image, dayworld aspirations, and career. Part of the shocking quality of Ernst’s composition is that this image pulled from the realm of dark dream is playing out in the daylight world. All this creates that strange, otherworldly effect, taking it out of reality, even if the light says otherwise.