“Photographing Black Lives Matter vigils through light-bending prisms helped me create radically gentle images of protestors and reflect on my own implicit bias.”

Images and text by Emily Geraghty.

As a visual journalist, I’ve covered identity politics for five years. I’ve developed a strong muscle for bringing cameras into tense situations. I’ve sat through mandatory corporate workshops covering expectations of privacy in journalism, and I’ve had no moral quandaries over snapping photos in public places. Still, bringing my camera to the Black Lives Matter protests in New York City in June of 2020 made me feel uneasy.

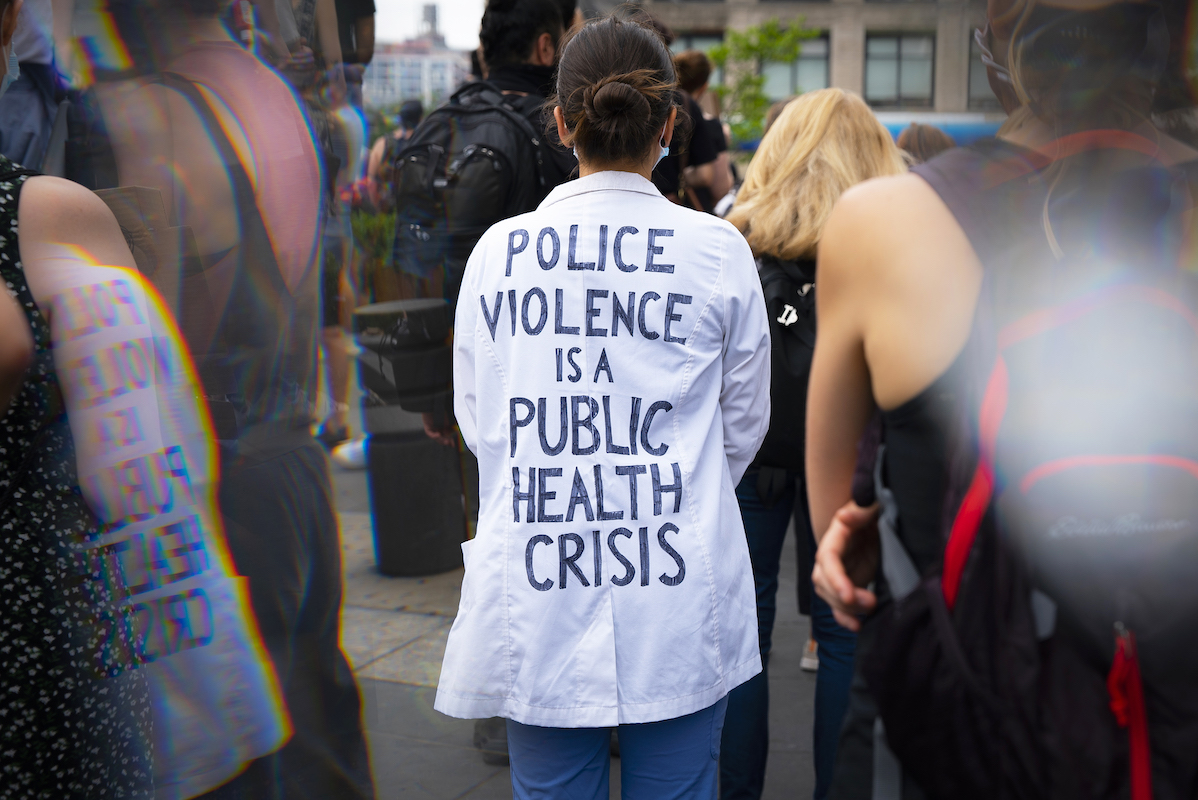

At face value, New York City had yet to start reopening amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and an 8pm curfew had been instituted after multiple nights of vandalism and police clashing with protestors. On a deeper level, I was concerned that as a white woman, it wasn’t my place to take photos of Black people mourning Black lives lost to police and systemic brutality. I was also constantly, validly being reminded through Journalist Instagram (maybe you’re a part of Teacher Instagram or Nurse Instagram or some other niche online space) that gatekeepers for Black stories have historically been white and the question of if it could cause harm to publish photos of protestors. Before I brought my camera to a protest, I wanted to consider how I was capturing these photos and why I felt inclined to photograph protests.

The images I saw in the news media from protests were harrowing. These photos portray events worthy of coverage, but the phrase “if it bleeds it leads” – a trope in journalism that suggests violent crimes are the most engaging stories – came to mind. Were images of looters and violence incited by the police themselves obscuring that most Black Lives Matter protests are peaceful?

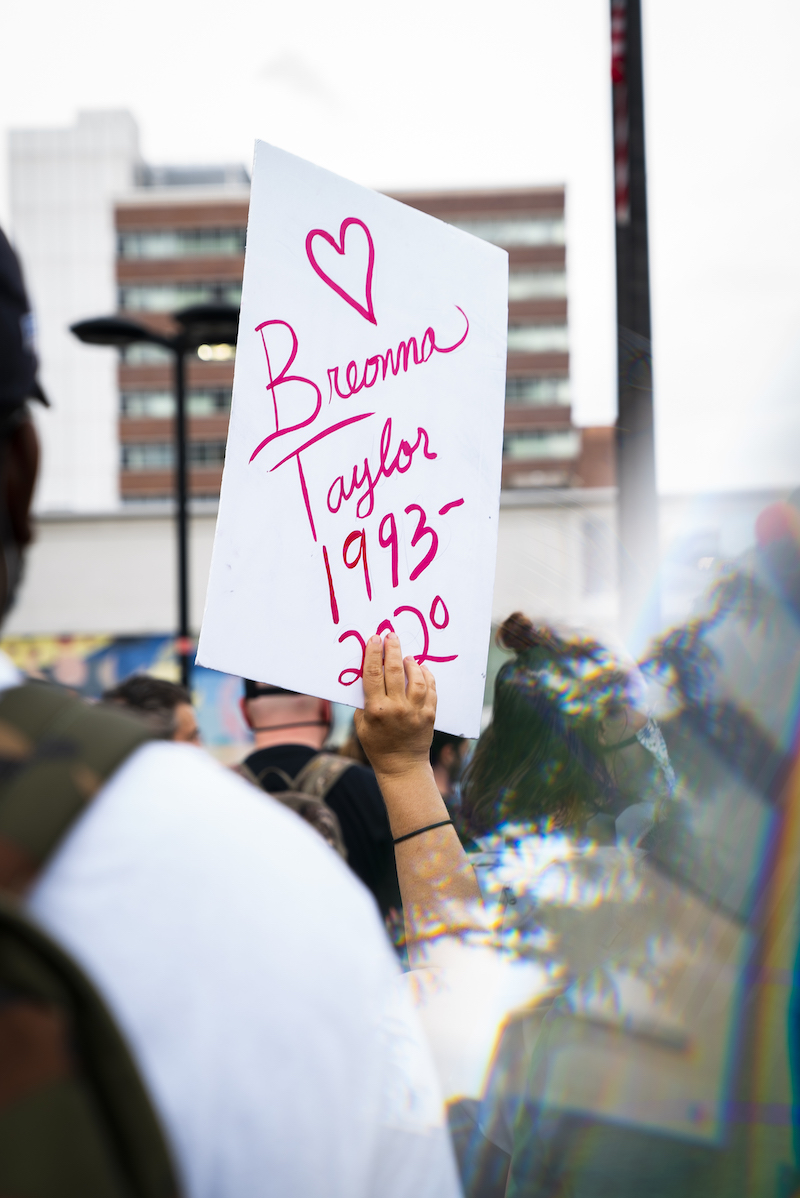

On June 6th, Breonna Taylor’s birthday, I decided to attend a vigil celebrating Breonna’s life and protesting police brutality. I brought my camera, but told myself that if the atmosphere didn’t feel appropriate for taking pictures, I wouldn’t. The vigil was held at the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building in Harlem. A massive statue of its namesake congressman towered over the crowd. I wanted to create images of attendees that reflected the peaceful, empathetic and determined atmosphere.

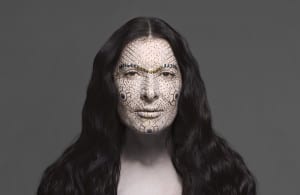

I took photos of attendees through prisms using the Lensbaby OMNI system. Placing prisms in front of the camera lens created soft, light-bending, multi-colored effects and an ethereal aesthetic. The radical gentleness of the attendees that brought bouquets of flowers and colorful balloons for Breonna was magnified by this technique.

Taking documentary photos in real-time with prisms can be difficult. Photographers need to hold the camera, which can be cumbersome on it’s own, and also hold delicate glass prisms in front of the lens at a precise angle that will bend light. The Lensbaby OMNI system makes documentary photography with prisms a lot easier. It’s a metal ring that attaches to your camera lens and includes detachable magnetic glass prisms.

I asked for permission to photograph people as often as possible, though with social distancing and the nature of protests, it wasn’t always realistic. Asking for permission when possible meant I interacted more with my subjects than when taking candid slide-of-life photos, and it felt like a level of trust was established between us. Was I nervous to ask Black people mourning the loss of Black lives if I could take their photo? Yes. Was it more respectful than not asking permission and taking their photo anyway, due to my own anxiety? Also yes.

Even though I went into photographing the vigil with a visual goal, I was surprised looking at the results and reflecting on my experience. When I looked at the photos I took of Black men holding flowers, balloons, and peacefully protesting, I had a visceral reaction. I realized how infrequently I see nonfiction images of Black men being tender. News media infamously portrays a distorted image of Black men as violent criminals, an image that does not accurately reflect arrest rates.

That instinctual reaction was a reminder that even as a journalist who’s spent their career passing the microphone to underrepresented and misrepresented groups, there’s still work I can do to break down my own learned implicit biases. According to the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, “implicit biases are not accessible through introspection.” Studies have shown that counter-stereotypic imaging as well as contact with people in different identity groups than your own can help us unlearn implicit bias.

Going a step further, it’s important that white people try not to get caught up in what the Perception Institute calls racial anxiety. It’s obvious that people of color may have racial anxiety about being discriminated against. Less obvious is that when white people are anxious about being perceived as racist, it can literally reduce our cognitive function. This makes it harder for us to learn and reason. Racial anxiety can make us avoid interacting with people of other races and prevent meaningful, personal conversations. Not conversations about race itself but interactions that allow us to know people as people and not assume who they are based on stereotypes. In studies about breaking down implicit bias, this is called individuating.

Had I not gone to the protest vigil for Breonna Taylor’s birthday and not asked permission to take photos of attendees because of my own racial anxiety (feeling like it “wasn’t my place”), then I wouldn’t have created counter-stereotypical images or interacted with people outside of my own racial group – two evidence-based ways to unlearn implicit bias. As a journalist with access to publication, had I not taken these photographs, I wouldn’t have disseminated the images to an audience who also has implicit biases to unlearn.

It is, without question, time for Black journalists, filmmakers, photographers, artists, writers – to tell the stories of Black people (or whatever stories they want) without the barriers of a racist, obstacle-course-of-bias system controlling their access to creation, publication and recognition. There are moments where white people will need to step to the side so Black and POC creators can receive opportunities to make their voices heard, and white people should work to make space for BIPOC creators in an industry where white people are the majority. I also believe that if white creators don’t make work that amplifies Black voices because it’s “not their place,” they will be doing a disservice to the movement for racial equity. It is misguided to think that making a homogeneous body of work based only around experiences the creator themselves has gone through helps make space for BIPOC voices. Just like it’s misguided to believe that by not interacting with people of other races, we don’t have biases because we aren’t actively offending people with our words and actions. If only minority creators tell minority stories, stories about marginalized groups of people will remain exactly where they are now – in the margins.

Emily Geraghty is a visual journalist and video director living in New York City. She has reported on identity issues for NBC News, Glamour, Allure and Teen Vogue. She won a 2018 Webby Award for her short documentary Pretty Big Movement Destroys Dancer Stereotypes. In 2019 Emily received a public affairs honor from her home state of Missouri for her work in inclusive media. You can see her work here.