(above) Hair standing on end, eyes narrowed, nostrils flaring, and teeth clenched, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled Head, 1982, grabs you by the throat. Photo by the author of work currently on view at the Brant Foundation.

People always ask why art is important to me, but author Bianca Bosker recently asked me why art is important at all. She has a fair point. Art can seem like the ultimate luxury, especially in the face of climate change, war, mass shootings, and Trump. Except it’s not.

Art is all about the experience. Owning expensive art is a luxury, but experiencing it isn’t.

That’s easy for me to say from my perch of white, socioeconomic privilege. So I’ll defer to Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was neither white nor (at least initially) privileged. A stunning array of the artist’s work is currently on view at the Brant Foundation. Whether you love or hate his childlike style, there’s no denying the immensity of its primal power. His work is art at its most universal. Hair standing on end, eyes narrowed, nostrils flaring, and teeth clenched, Untitled Head grabs you by the throat. In two dimensions, Basquiat embodies the combination of fear and rage we all feel when we’re threatened. His depiction of flight or fight is so recognizable that you might instinctively recoil from it without even knowing why.

Art is influencing you, whether you realize it or not. A picture says a thousand words…just try writing a sunset.

Images are the best communication devices. Their strength means that art has always shaped society. Chinese characters are images of the concepts they represent and vice versa. Egyptian pharaohs awed their people with monumental sculptures of themselves and their gods. The stained-glass windows in Notre Dame aren’t just beautiful. The windows illustrate biblical passages that taught illiterate peasants the basics of Christianity. Islamic art, with its lack of figures, constantly reinforces its prohibition against idolatry.

Hilma af Klint’s record-breaking show at the Guggenheim brilliantly demonstrates how visionary artists communicate new ideas to the rest of us. By nature, artists are more open to new ideas than your average Joe. Af Klint studied theosophy, which developed in the late 19th century. Early in the 20th century, theosophy’s influence led both her and Wassily Kandinsky to express themselves in a completely new visual language. They’re the first known artists to make abstract art, but they didn’t come up with abstraction together. They didn’t even travel in the same circles. Although af Klint might have known about Kandinsky, she started making abstractions years before he did. And he almost certainly didn’t know about her because she rarely showed her abstract works and even stipulated that they shouldn’t be exhibited until 20 years after her death. So it’s highly unlikely that they influenced each other. Instead, they both absorbed the intellectual zeitgeist of their time and expressed it in a radical new way.

That’s what artists do. They reveal and communicate the profound. In turn, the rest of the world’s creatives use music, literature, and visual art to inspire their work. High culture eventually filters down to everyone through pop culture, advertising, and fashion.

Meanwhile, ease of creation is heightening the cultural primacy of the image. Instagram, emojis, and memes transcend boundaries. Since visual art is the production of the most meaningful images, that means it’s becoming more important, not less.

Art allows you to experience other people’s perspectives. At a time when our world is increasingly globalized and polarized, we need every tool we can get to help us walk a few miles in someone else’s shoes.

I know the good and bad of living life as a woman. I also know intimately what it’s like to be lower middle class, middle class, and upper class. But I’ll never know what it’s like to be a black man in America.

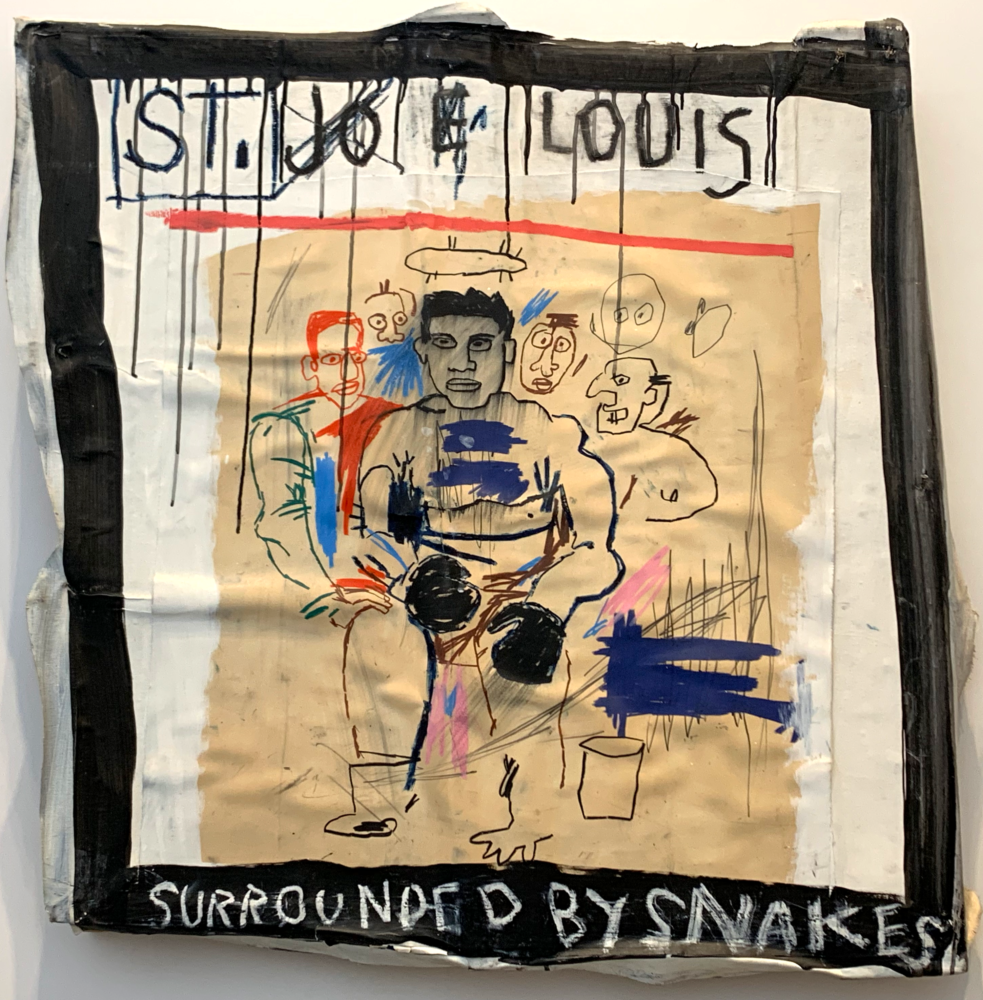

Experiencing Basquiat’s work helps me understand that perspective better. His frenetic male figures are almost always steeped in angst. Their fists are raised in frustration even when he depicts them heroically. His series of works about successful black men are especially eye-opening. He painted them with symbols of honor, like crowns or halos. But sometimes, as with the boxer, Joe Louis, they look like crowns of thorns. He always coupled the status they earned with trappings of martyrdom. These themes echoed his own struggles as a successful black man in a world of white privilege.

Basquiat also used art to shine a brilliant light on the gamut of social justice issues. He called attention to colonialism, income inequality, oppression, systemic racism, economic exploitation, and police brutality along with the fear, frustration, and anger they breed.

Like me, you might not have the artistic skills to change the world, but by experiencing art, we can open ourselves up to feel more empathy for others. Art is one of humanity’s best hopes for healing our gaping divides.

Holly Hager is an art collector and the founder of Curatious. Previously an author and a professor, she now dedicates herself full-time to help artists make a living from their art by making the joys of art more accessible to everyone.