Identity is a vast topic. Included in its folds are celebration, tradition, food, culture, music, politics and family. Today, many members of cultural identity groups also find themselves reckoning with collective trauma almost as zeitgeist.

Perhaps instigated and inflamed by the current pandemic and political tension, societal unrest can amplify trauma for those who are survivors of abuse, whether systemic or otherwise, in their own lives.

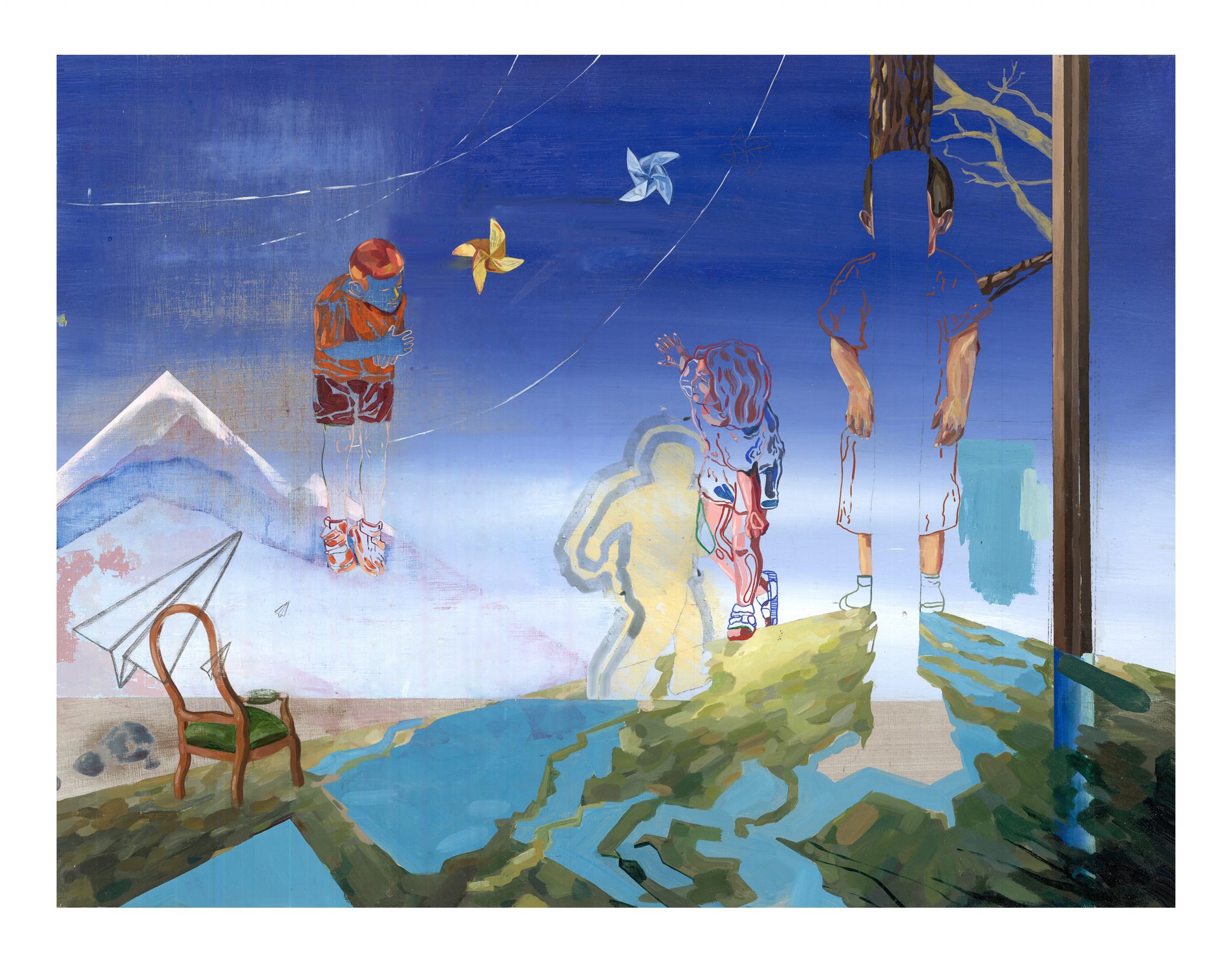

Through her interdisciplinary use of materials and process, Colombian-born artist María Durán Sampedro dives into compassionately exploring the experience of trauma survivors. Her sculptural works involve a process of casting and layering that embraces imperfection and allows for chiseling away and unraveling generational trauma. In contrast, her paintings involve a process of layering acrylic paints to create a multifaceted history, one in which histories are built and added upon rather than stripped away.

Read below for our full interview with María Durán Sampedro.

AZ: What role does your Latinx heritage play in the subject matter you explore in your artwork? What about the legacy of colonization in Latin America in general?

María Durán Sampedro: From its inherent colonization, Colombian history has been filled with a legacy of pain and sadness brimming from armed conflicts, guerrillas groups, and devastating poverty. My practice focuses on presenting the pains that are imperceptibly affected: pains that are not necessarily obvious like an injury or the absence of a loved one at home.

Despite the great violence that floods our history, I have the strange responsibility and luxury of portraying those pains that can be ignored or put aside because they do not immerse like death or displacement, at least not always. But I can focus on giving mental disorders, and the life of a survivor of physical or psychological abuse, a space to be recognized and embraced in compassion.

Due to the urgency and stresses that rig my country, shame and stigma against mental illness and pervasive misogyny can often be overlooked. I firmly believe that pain is inherited and is linked to our genes and cells. My own experiences of abuse are a testament to the fact that it has strained many generations.

I am sure that every Colombian has been impacted in some way by the uncertain violence in my country, and simply because I am Colombian, my work will be tinted with it. But I seek to give place to hidden duels and universal problems that affect us all. Perhaps the history of Latin America and the society in which I grew up has allowed me to recognize and inquire about other human regrets.

AZ: Is the materiality you utilize of particular significance to the topics you explore?

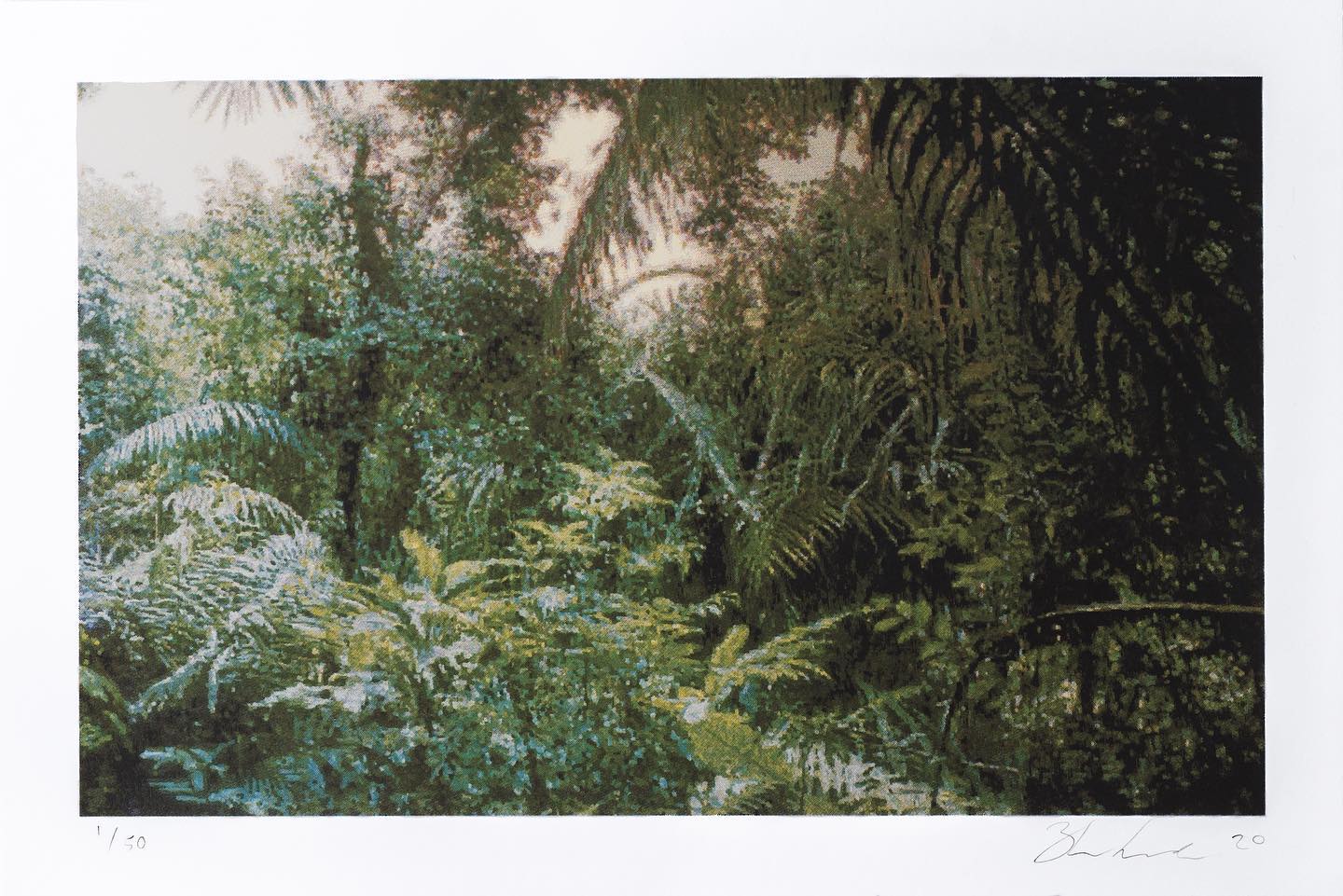

MDS: Yes, absolutely. But more than the choice of materials, the process of applying the materials is what imbues them with meaning. I utilize acrylic for my paintings, and various casting materials including wax, resins, and epoxy clays for my sculptures.

When I paint, the resulting image rests on top of multiple layers of paint (an older painting or two, gradients, or textures). I build on top of various layers to create histories on which the image draws upon. Often I will sand away to reveal some of the painting’s past, and paint over to obscure or highlight the new and old. On other occasions, I will replicate an image in fragments.

This behavior is similar to the mechanics of memory. Sometimes when we repress painful memories hiding them in corners, we re-create the same images to obsession or get struck by an uninvited flashback. This is especially true with memories of a severe emotional charge, such as a traumatic memory or unwanted information. Through this image-making process, I seek to echo the psychological grappling that loops in our head due to trauma.

When I am creating my sculptures, the casting process can be a bit improvisatory. Once the material has been poured into the mold, I do not seek to correct imperfections on its surfaces. I enjoy this aspect of my process immensely because these imperfections are beyond my control and resonate with the inevitability and painful surprises that attack our existence.

But despite these ruptures and corrugated valleys that form, the figure supports itself and composes itself in our physical world to be recognized and welcomed in its complete imperfection. Through my sculptures, I hint to pain, but I seek to signal in them the fearless resilience and strength that is exacted from survivors of abuse.

AZ: Regarding bodily trauma and the loss of innocence. How do you define innocence, and furthermore how do you explore such a deeply sensitive and personal topic without re-traumatizing survivors? When viewers experience your work, what do you want them to feel?

MDS: Innocence, to me, is the veil with which children outline the world. They naturally see it in the most idealized way, without any instinct to disturb the world’s vision with cynicism, uncertainty, or violence. Innocence is exaggerated, warm, invariably kind, earnest in her love, and can be reclaimed in adulthood.

The task of not retraumatizing or generating triggering content is one of my most pressing responsibilities. I always keep it in mind. In my pieces, I seek to avoid the “original violence” and focus on the survivor’s experience after that “original violence”. As we age, ordinary days continue stacking on to each other.

It is no surprise that horror has an extraordinary power to jolt us out of our mundanity and into big headlines and packaged tearjerkers. Under these boxes, innocence is vulnerable, and survivors are fitted as victims and nothing more. Because of this, there are no concrete traces of brutality in my work but hopeful recognitions of strength and tenacity.

To reclaim innocence, the struggles that come with losing it needs to be recognized. It sounds strange, but the way out of shame is to talk about it; unearthing the “secrets” of abuse in a trustworthy environment frees the survivor from carrying that burden alone.

Victims of child abuse have a barrage of symptoms to fight that haunt many of us throughout our lives; problems such as substance abuse, endangering behaviors, depression, anxiety, intimacy problems, and living with a false sense of self. Many of these experiences warp into a shame that many never share, and help drown an internal tumult.

In my pieces, I look for the survivor to recognize an inner fortitude, know that they are not alone, generate awareness of the ubiquitous attack on innocence, and hopefully start conversations that lead to healing.

AZ: The exploration of trauma is particularly powerful coming from Bogota, a capital city that has seen its fair share of political and state sanctioned violence, even as recently as this month when a man was killed during an incident involving the Colombian police. In what ways do you see the trauma of this type of social and political unrest mirrored in American society?

MDS: The parallels are very damning. On the night of September 9, Javier Ordoñez died under police custody, pleading for his life after continued tazing. This was shared on social media. Amid the following protests in Bogotá, at least 8 more young protesters were murdered.

These eruptions have been bubbling since the beginning of COVID-19, but abuse of power by the police has been the norm for as long as I can remember. Both North America and Latin America are full of sadness right now. COVID-19’s pause has led to an awakening around systemic injustices in our institutions, both in the USA and Latin America.

News of police brutality against Black Americans has spread throughout the world, spurring this global awakening. Additionally, the media and the government’s highest representatives, Ivan Duque and Donald Trump, assist with congratulatory rhetoric to the same forces that are seen hurting people in the streets instead of protecting them, generating more anger in our forced sedentary lifestyle. These and many more wrong decisions have given us these injustices.

But our collective trauma has propelled us to seek change. In both societies, and many corners of the world, the vitality of inquiring and addressing the manifestations of injustice and racism in our communities has never seemed clearer. We have realized that our countries belong to everyone and are made by everyone, and that endemic ignorance and racism must be fought on all fronts starting with ourselves. Otherwise, the unnecessary losses will never stop.

María Durán Sampedro is a Domingo Comms Featured Artist. Head to their website to learn more about Sampedro along with other featured and Latinx artists.