Los Angeles-based gallery Garis & Hahn recently opened project 0052, an exhibition by Spanish, conceptual photographer, Felix R. Cid. entitled The Sword of Damocles. We caught up with Felix to discuss his latest exhibition, process and his thought on the current political landscape.

AZ: What’s your morning routine?

FC: I don’t really have a routine. It’s been a very complicated and busy year. I wake up not early, never at the same time, and often in different places. But the first thing I always do is have a green juice and go to the gym. Then I usually go to the studio.

AZ: What is the background on your phone?

FC: It is a picture from one of my pieces. The piece is on my website, and its called Pan-De-Mo-Nium.

AZ: Share some of your favorite Brooklyn spots?

FC: You know I don’t really go out that much, but I love the Union Pool. I actually go there quite often.

AZ: Why did you think the “Sword of Damocles” is an apt metaphor for your piece?

FC: I don’t know if I would call it a metaphor, it’s a title. There are a lot of specifics about this time and project that my work has not embraced before. It feels like this work is more strategic, it’s more put together, more compacted. It has a message to send. Living through this year has influenced my work greatly. At first, it was not easy for me to make sense of the sculpture and photographs together, so I thought that this title and myth represented the connection between them. Power being challenged through protest and the destruction and danger that powerful figures often face.

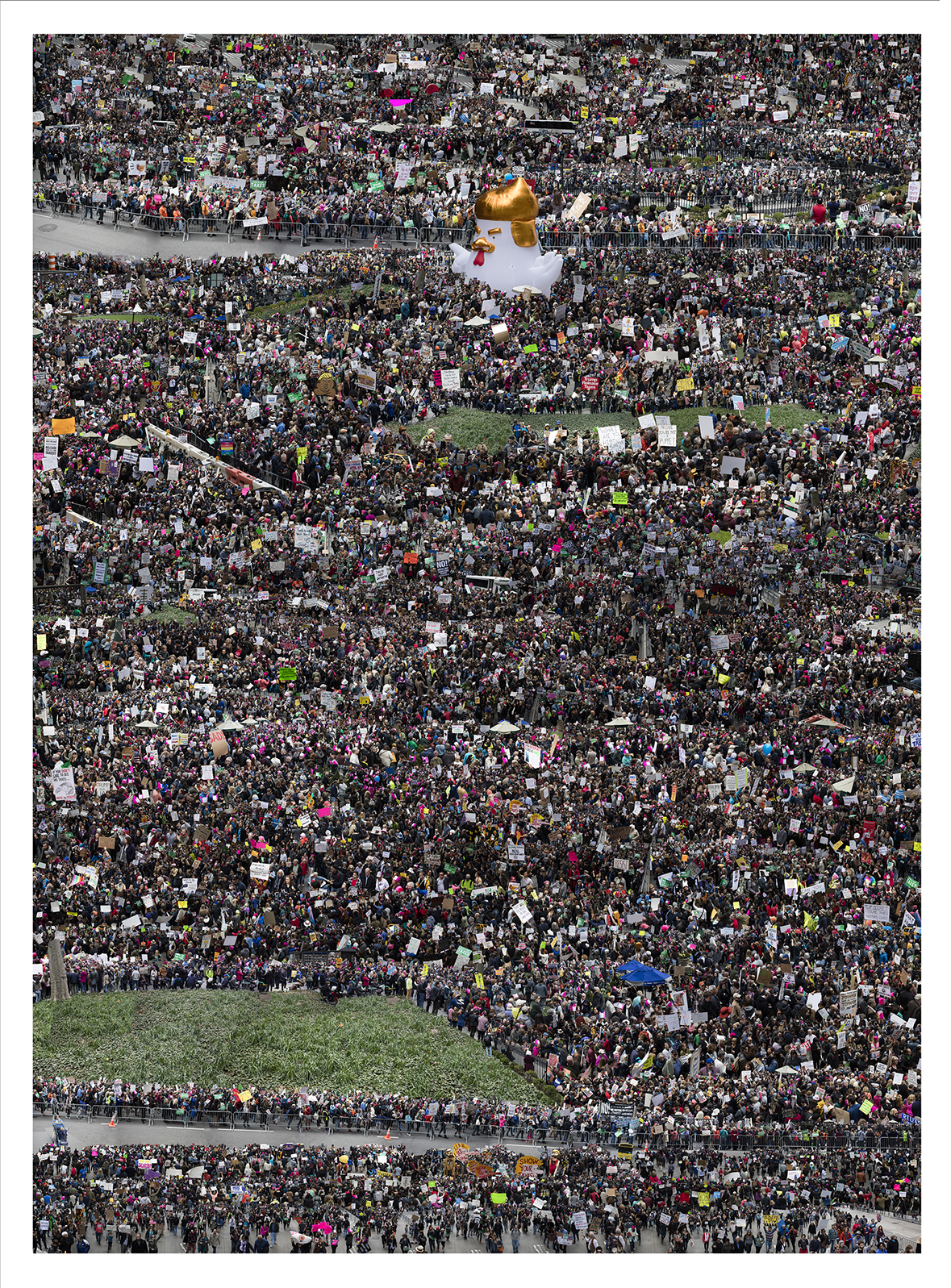

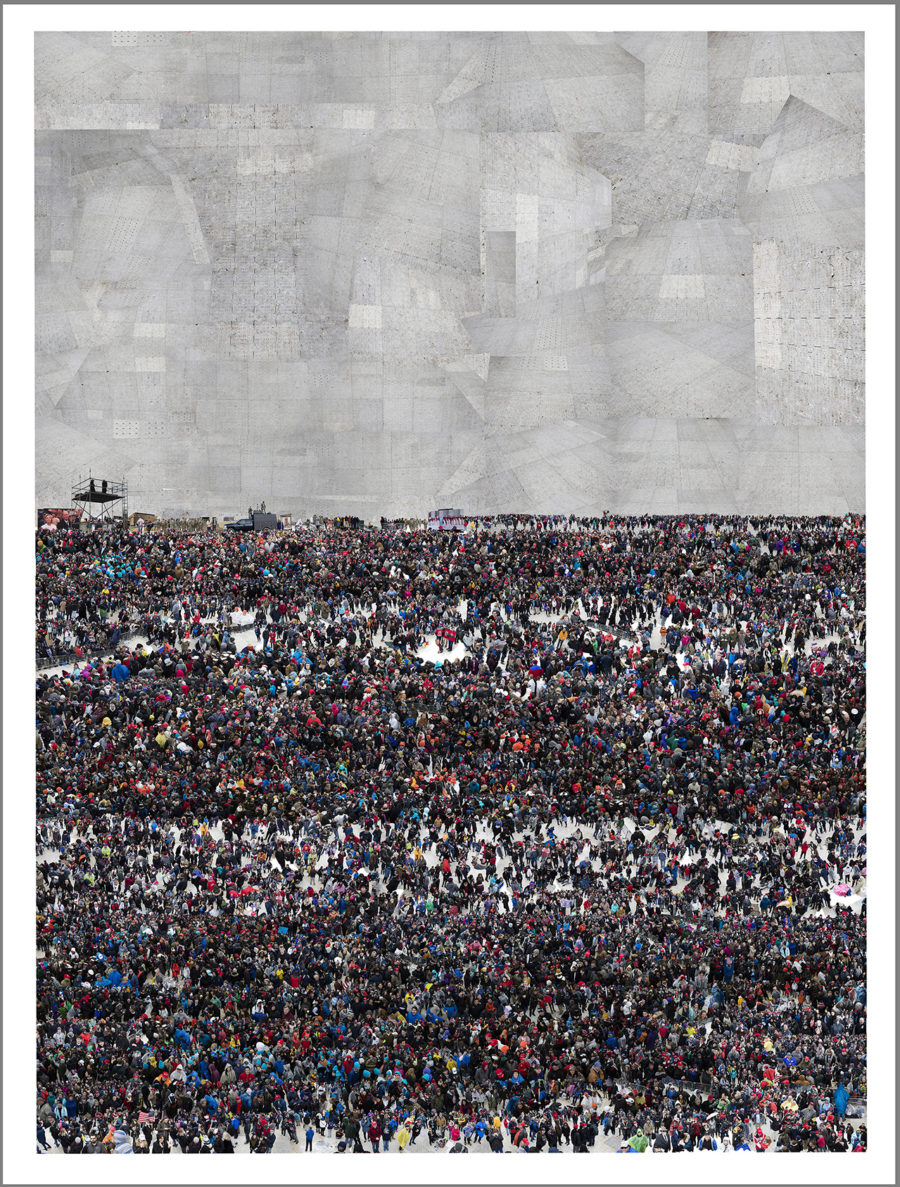

The things that I have been photographing are protests and rallies including the Trump Inauguration and Women’s March, both of which reject the patriarchal society that we live in Desire for power and attaining it, greatly influences society’s view of you. The more power you have, the more under threat you are.

AZ: How has your exhibition been influenced by the current political climate?

FC: I was educated in photography. I started photography before grad school and I have been a photographer for almost 20 years now. I had a business, I worked as an assistant, etc. I was photographing in Ibiza for a while, shooting almost 800 people a day at this touristic building. I am not a studio photographer, I’ve always been out there in the world or I wasn’t. I don’t know if I am becoming that now. The last few years I did project X, which is very similar to this project, or the process is. I photographed massive crowds. Then, I would go to the computer and make a larger picture from them. I was doing this for a certain reason, certain formalistic aspects of photography. Then I got tired of the project. If you look at my website, my work is really not like this. I do a lot of studio photography now, too. I was working in the studio, and then this happened. Trump gets elected and it was very depressing for many people. And to be honest with you, I was working on a very different project, I was almost done, I had been working on it for two years. I decided to put it aside. I felt like I would be of better use out there with a camera in that climate and context. I felt like I couldn’t stay inside looking at the news. I know how to work with the crowds and thought maybe I could do something.

When I started working on this project, I saw something, which I know how to recognize in my work, that the content could inform my process and my message would be very clear to the public. The quality of the photographs is insane. I work with a very high-resolution camera. You can see the eyes of the people. It’s hyperrealistic. When you start coming out of it, the piece becomes more and more abstracted and you don’t know what you are looking at. The form is abstracted. I thought that, metaphorically speaking, it was a very interesting thing that was happening with the work and process. It’s kind of a visual metaphor of how I feel that the political climate and entire world of information functions.

AZ: What is the significance of the repetition in your images/collages?

FC: To clarify, no one single photograph is repeated. They are all individual. But often, you can find the same person twice in the photograph. If I am shooting the crowd, I may photograph one guy, and then he moves and he is photographed again from another perspective.

This causes the viewer to question what he sees and what he thinks he knows. The reason why I accumulate so many images and work this way is for the drama. I am interested in drama. The photograph has no narrative by itself until you add another photograph. When you accumulate hundreds of photographs, you can maybe trick/create the narrative. It’s like an entire movie is placed inside of one frame. You’re always going to discover something else. Ultimately images are repeated to help create this narrative.

AZ: We enjoyed your 2015 “X” exhibition, was this the first time you experimented with this process?

FC: I started to make X in 2012, right after I graduated. It took me almost three years to make and it came out in early 2015. I was very broke and trying to find work, but I got a couple of grants and that’s when the project started to develop. But before X, I did something that informed all of this.

While I was in school, I did a series called black photographs. I made a triptych, which represented different aspects of Spanish society — there was a bullfight, a protest in Madrid, and a foam party in Ibiza. These were also made from a compilation of various photographs that I took over a few days. The bullfight imagery uses photographs from three different bullfights, same with the protest and same with the foam party. To make a long story short, this was the first time I was working with digital photography. Up until then, I was working with film and I was obsessed with it. Then, to be honest, I broke my camera, I didn’t have a lot of money and I bought a digital camera. I started to work outside the single frame because there is no limitation with digital cameras, viewing, and editing the pictures are free. I started to compile the digital images in the same frame and found that it related well to what I was interested both visually and thematically — reality, perspective. I also realized that if I was going to print something there had to be a reason for it. Why make a print if you could view the photograph through a screen, like we do every day of our lives. However, the photographs I was making needed to be printed. There was no screen, at least then, that could give you the same experience because of the massive amount of detail.

AZ: How long does it typically take you to compile hundreds of digital photographs to create one piece?

FC: It depends. It obviously takes a lot of time. Often the process takes months. Like with everything else though, I never work on one piece at time. I work on one for a while and when I get tired, I switch. When I get tired of that, I switch back. This time though, I didn’t work on any other projects. I worked on the various aspects of this piece for almost a year straight.

AZ: What’s your background in sculpture? Are you self-taught?

FC: I have zero background in sculpture. Of course, I am very privileged to have a great education in the arts. But this is the first time I worked in sculpture, which was a huge risk. I started to make busts about two years ago, and I put them up in Miami at an art fair. A very influential collector bought one, and that was very motivational for me. I also wanted to add another medium to this project and sculpture seemed to be appropriate. It brings the work out of the frame.

AZ: You use image editing tools to distort and piece together your photographs. How does this distortion/blurring of reality inform your work?

FC: I don’t distort or manipulate any image. I use Photoshop in the most essential way. I use it to cut out images and I probably only use three tools. Anybody could do what I do with Photoshop. I have a lot of friends in the fashion world and they tell me that I should retouch my photographs, but I am terrible at it. I use Lightroom to separate, edit, and compile the images.

I feel like these works are like paintings. When you paint, you go and buy the paints that you want to use and you make choices with them. It’s the same process with my work. I don’t take photographs, I make them. Often, and especially at openings, I have people come in and say “Felix, where were you when you took this picture?” They believe that the picture was a scene that existed in the real world. We use photographs to sell products in our western, capitalist society. They mimic reality. When you look at a photograph, you believe what is in the picture. This fascinates me and it plays with the question, “What is reality?”

AZ: Have you found that your upbringing in the shadow of the Franco dictatorship informs your art?

FC: I grew up in a very leftist, progressive, working-class family. My parents were socialists, and my grandfather was a communist and fought in the Spanish Civil War. (Unlike in other cases, Socialists were the good guys in this war.) He had two pieces of metal in his body and was in three concentration camps. I grew up in a very political environment. When I was younger, I considered myself an anarchist. I don’t consider myself an anarchist any longer. I have found that I am more interested in the philosophical aspects of politics and history, which has greatly informed my work.

When I moved to the states, I was very surprised about the lack of youth involvement in politics, compared to where I come from. I never really understood it. It seemed that people didn’t really consider their privileges and freedom until Trump was elected. Now everybody is interested in politics.

AZ: You’re from Spain originally, what is your take on the Catalonian independence movement? How do you think this relates to the political climate that you’re depicting in The Sword of Damocles?

FC: I actually have a new piece about this that is not in the show. I haven’t finished it yet. I went to Barcelona and photographed the streets during the protests. I have never seen anything like this Spain since the protests in 1982. It was overwhelming and very different for me. I had to be careful because I am from Madrid. I’ve been to Spain three times in the last month to document the protests and interestingly enough when I returned to Madrid the facades of the buildings were covered with Spanish flags. They were hanging from out of windows and from balconies. And for Spain, because of the dictatorship, the flag has never been a symbol of democracy or unity. It has been very closely tied to the dictatorship and conservative nationalism. So of course, I started to photograph to this. It was incredibly interesting to see people that would never before hang the Spanish flag, having it flying out of their windows.

In my opinion, this has been an absolute abuse of power. The minority has taken advantage of the majority, but things are complicated and people are frustrated. I just don’t understand. What I do know is that Spain is experiencing an economic and cultural peak, and we achieved this by working together, so why is there an independence movement now? The same goes for the world, which is also experiencing an economic and cultural peak, which historians and philosophers say is a product of globalization.

AZ: What’s next for you?

FC: I have a show in January in Madrid for this work. We will then probably go to Saramago in February and then Miami for the art fairs. I’m trying to set up a New York show too, but I haven’t found the right venue yet. I am heading to Europe now and going to spend some time working in Ibiza.

AZ: How can we stay in touch?

FC: I have my website www.felixrcid.com and an instagram, @felixrcid.

The Sword of Damocles is on view at Garis & Hahn, 1820 Industrial St, Los Angeles, CA through December 16, 2017.

photos // courtesy of the artist, Garis & Hahn